Zero Waste Fashion Design

Scraps of fabric have been used by artists and craftsman throughout the world to varying degrees for centuries. The word, "scrap," can be defined as a rejected piece of a larger whole, and usually connotes a sense of uselessness. The tradition of using an entire piece of fabric down to the selvedges, in contrast to a process that produces scraps, is akin to using every part of an animal carcass for food and other functions. This practice can be traced back to necessity and/or religious beliefs. In the case of the Indian sari, a piece of fabric left whole is considered holy. This parameter gave way to the calculated wrapping technique used for draping the sari onto the wearer.

Contemporary uses of scraps can often be linked purely to aesthetics. For example, high fashion Japanese brands such as Kapital, and Komoro are incorporating references to boro in their products. Boro is an early nineteenth century patch working style developed by rural Japanese during a era when cotton was extremely scarce. This material limitation is no longer an issue for designers, however, and what remains is the symbol this style represents for the consumer. What is lost in this modern homage to the traditional boro style is the intent to maximize functionality and minimize waste. Contemporary designers face the responsibility of communicating to the consumer the origin of the references they decontextualize. Increasingly, designers are stepping up to this challenge and not only referencing techniques for aesthetics, but also incorporating these techniques into their design and manufacturing processes.

Textile waste is an increasingly critical issue in the fast fashion industry, one which is causing devastating harm to our environment. The fast fashion industry discards roughly 15% of the total fabric it consumes. A pattern layout is considered “less” wasteful if more than 85% of the fabric is used. Fortunately, with the help of new technologies, forward thinking designers, and age old techniques, there are many options for bringing this percentage down.

Just as there are often many solutions for a single problem, zero waste design is one of many options designers have for developing more sustainable manufacturing processes and products. Other solutions such as recycling and upcycling can be incorporated with zero waste design as well; sometimes there is even overlap between the two.

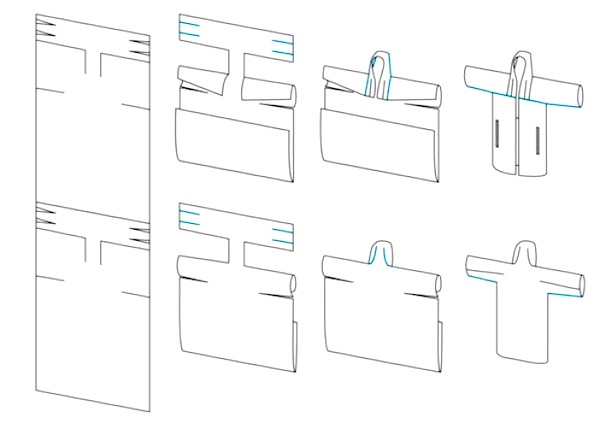

"Zero waste design," or, "zero waste pattern making," as its sometimes called, refers to the practice of designing patterns for clothing with little to no fabric waste. This is achieved through careful pattern layouts and creative solutions for eliminating awkward curves that leave too-small scraps left on the cutting room floor. The term is intentionally vague and is being adopted by designers who are using various techniques, materials, and technologies to achieve the “perfect” zero waste garment.

Although the term, "zero waste design," is relatively new, artists and craftsman have been using similar techniques for centuries in order to conserve precious textile material. The driving force behind the Japanese boro tradition was poverty and extreme necessity for preserving textiles as opposed to aesthetics. The boro style, meaning, “tattered” or “ragged,” emerged in rural Japan in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century. Both the First and Second World Wars played a major factor in the depletion of resources such as cotton within rural Japan. To protect themselves from the cold, the women in the families would use scraps of textiles and patch them over holes in older tattered textiles combined with a stitching tradition called, "sashiko stitching." These pieces were passed down to children and, over generations as the layers would build, the original fabric became virtually indistinguishable from the patchwork. After World War II, as Japan recovered, the boro style clothing that remained became a reminder of the hardship people had experienced. As mentioned before, some renowned Japanese brands are carrying boro into the 21st century and embracing the harsh reality it represents. The question here remains that if the companies are producing for aesthetics rather than necessity, what is left of the original boro style?

Meanwhile, in France, at the turn of the century in the studio of French designer Madeleine Vionnet, a similar intent to conserve materials was being exercised. Vionnet was born in Chilleurs-aux-Bois on 22 June 1876, and founded her fashion house in Paris, France in 1912. She was forced to shut down after just two years due to the onset of the First World War. Vionnet was able to reopen in the 1920’s and had earned an enormous following by 1923. Due to the onset of the Second World War in 1939, she closed her fashion house. She was 63 years old at the time. There is no doubt that being sandwiched within the context of not one, but two, major world wars shaped and defined her pattern making and design techniques. Clothes and fabric rationing began on June 1, 1941, two years after food rationing started. Designers such and Balenciaga and Vionett were forced to consider excessive fabric use within their designs.

With her innovative approach to pattern making and experimentation with draping, Vionnet not only earned the title “architect among dressmakers” but also tapped into an early approach to zero waste design. A product of the industrial revolution, she designed for efficiency and sought to minimize the amount of work involved, while upholding excellent standards for the final product. Her efforts yielded elegant results leaving an indelible mark on the fashion industry and generations of designers to come.

One of her major influences is on contemporary designer, Timo Rissanen, who wrote his undergraduate thesis on Vionnet. Risannen is a Finnish designer/artist/educator and has spent much of his career innovating upon zero waste pattern making techniques. He completed his practice-based PhD on zero waste fashion design, and has published a few books on the subject. Of Vionnet he says, “Vionnet seemed to be endlessly fascinated by the possibilities created by the combination of fabric, the moving body, and gravity, and that is something that has stayed with me ever since I was a student.” Risannen’s focus is on achieving the highest yield and/or least waste possible from a pattern layout. This involves inventing creative ways of draping fabrics over the body, oftentimes working without shortcuts like curved cutouts. The challenge in this is that the human body is made entirely of curves with no straight lines present. Rissanen is an Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Sustainability at Parsons School of Design since 2010 and continues to research waste and zero waste design within the realms of the fashion industry.

Contemporary examples of zero waste garment making range broadly in technique, process, and material. For example, Francoise Hoffmann works with felt and a technique called, "nuno felting." This technique allows Hoffman to both work with textiles and eliminate seams and darts, making it possible to make 3 dimensional pieces without sewing. One of the many unique features of felt is that the fabric is created at the same time as the design. Felt from wool is considered to be the oldest known textile. Considering this and the fact that contemporary designers such as Hoffman are recognizing its utilitarian value, is indicative of the plethora of techniques and traditions that early humans developed in order to survive the cold and other environmentally driven obstacles to survival and comfort. If we can draw upon this vast knowledge in the coming decades and innovate upon traditional techniques, there is no limit to what can be done to cut down on textile waste within the fashion industry.

The fast fashion industry is quickly depleting natural resources and soon waste will no longer be an option. There are new and emerging technologies that will provide solutions for designers and manufacturers. For example, knit waste can be avoided either by knitting each garment piece to shape in what is called, "fully fashioned knitting," or with 3d or whole garment machines that can create complete, three-dimensional garments in a single, no-sew process. The fact that there is no singular approach to zero waste fashion is arguably the most interesting part. At the very core of zero waste fashion design is the tradition of valuing materials enough not to waste them, and placing experimentation and innovation above the low standards set by a waste ridden industry.

References:

Scraps: Fashion, Textiles, and Creative Reuse. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2016.

Koide, Yukiko, et al. Boro: Rags and Tatters from the Far North of Japan. Aspect, 2008.

Wellesley-Smith, Claire. Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art. Batsford, 2015.

Brown, Sass. Eco Fashion. Laurence King, 2010.

Yen, Jessica. “Zero-Waste Design.” Seamwork, www.seamwork.com/issues/2016/05/zero-waste-design.

“Madeleine Vionnet.” Vionnet, www.vionnet.com/madeleine-vionnet.

“All About Boro - The Story of Japanese Patchwork.” Heddels, 21 Oct. 2015, www.heddels.com/2015/08/all-about-boro-story-japanese-patchwork/.