WIP Artist Highlight: Teri Gandy-Richardson

Julie Schumacher, Artist Programs intern at TAC, got together with May WIP resident Teri Gandy-Richardson:

Can you tell me a bit about your work?

I'm an abstract painter—a colorist, lots of layers. I used to work in acrylic paint, layering thin layers of colors on top of one another. I never liked stretched canvas. Before I started working with denim, I was working on plexiglass boxes that I glued muslin to. So it was kind of like painting on a sanded ice cube. The light would go through the panel and the thin coats of paint. I had basically gotten to the point where I felt like I was painting the same painting over and over again.

I would always collage in between paintings. I’d done a big show in Miami and just felt like I needed a break, needed to do something else. I wanted to do something more than collage. I looked in the corner of my studio and had a stack of Levi's I couldn’t wear anymore, but couldn’t get rid of either. So, I thought, okay, let’s do something with these. I started painting on them first. I was dissecting them—just the leg panels, even did one that was shorts. Stapled to the wall, they felt like human pelts after a while. My painted forms were kind of like liquid fossils—rocks and bone looking—so on the side of a pant leg, it started to feel like muscle and bone. It was cool and eerie and bizarre.

I grew more curious about working with this material and found a denim source in California, because after a while, I ran out of mine, my ex-boyfriend’s, and friends’. I started to see different patterns in how people wear their jeans. I'm short—my hems are always frayed. Some people always wear out the knees. Some people put their keys in their front pockets, so there’s a hole there. Some people wear out right across the butt. The different ways that people wear their jeans started me thinking about how that is such a unifier. Everybody has a jean story. Everybody wears jeans, and that is a way we’re all connected.

I was born in Minnesota. My first pair of Levi’s was a hand-me-down from a neighbor. It was a rust-colored corduroy pair of cutoffs with a tear under one of the back pockets. I was probably seven or eight. I got one of those denim iron-on patches and did it myself. It was part of childhood—jeans, being barefoot, climbing trees and running in the grass. As a kid, my bike was a light blue 10-speed Schwinn with a denim seat and denim-wrapped handlebars. I never knew I was going to work in denim, but when I started, it felt natural. I had memories and a love for the material. It made sense to keep going, learning more.

price tag reads: “When someone works for less pay than she can live on…she goes hungry

so that you can eat more cheaply.”—B. Ehrenreich, “Nickel and Dimed”

I started thinking about humans wearing this particular garment. I knew denim had always been a work garment. Starting from current times and going backwards, I was inspired by migrant workers, hard-working people wearing denim because it lasts long, and stands up to hard work. You can wear it forever, and the more you wear it, the more it molds to your body. It becomes more comfortable, a second skin. I thought about workers—those who put garments together, sell them, and collect the materials to make them. That whole chain brought me back to slavery times.

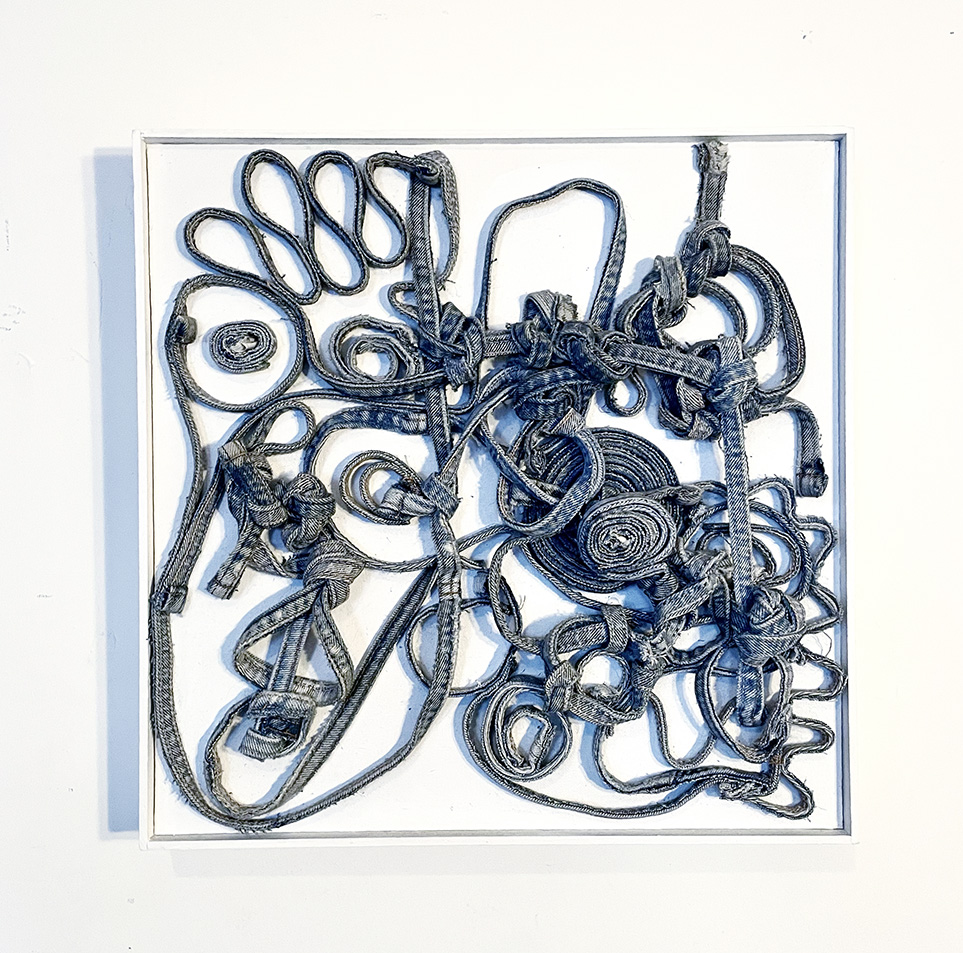

I started creating pieces that depicted what I was learning, and also moved towards a way of working more related to how I painted. I’ve done two-dimensional work and three-dimensional pieces. They started off by taking denim jeans apart and figuring out what language I could create with the pieces. I played with doodling. I took all the inseams out and drew with them—just scribbling more or less with the inseams.

Tell me more about how your discovery of the roots of denim has influenced your approach to your work. How does that history factor into how you compose and what you think about?

Looking back at history, I found that indigo plantations were so toxic that when enslaved people ran away and were caught, they were sentenced to indigo plantations. The life expectancy there was not more than seven years. It was that toxic. You could always tell who was working in indigo—their arms were dyed blue. They used paddles, but also their arms to mix, and it absorbed into their bodies. Even the irises of their eyes turned blue. Within seven years, they were dead. To commemorate that horrifying truth, I created a work called Stir, (Seven Years). It is a bouquet of seven pairs of denim arms made of pant legs that hang from the ceiling, also referencing “strange fruit” and the barbaric act of lynching, only officially criminalized in 2022. Underneath lies a dark blue denim mat with multiple denim hems standing up to depict a swirling vat of indigo.

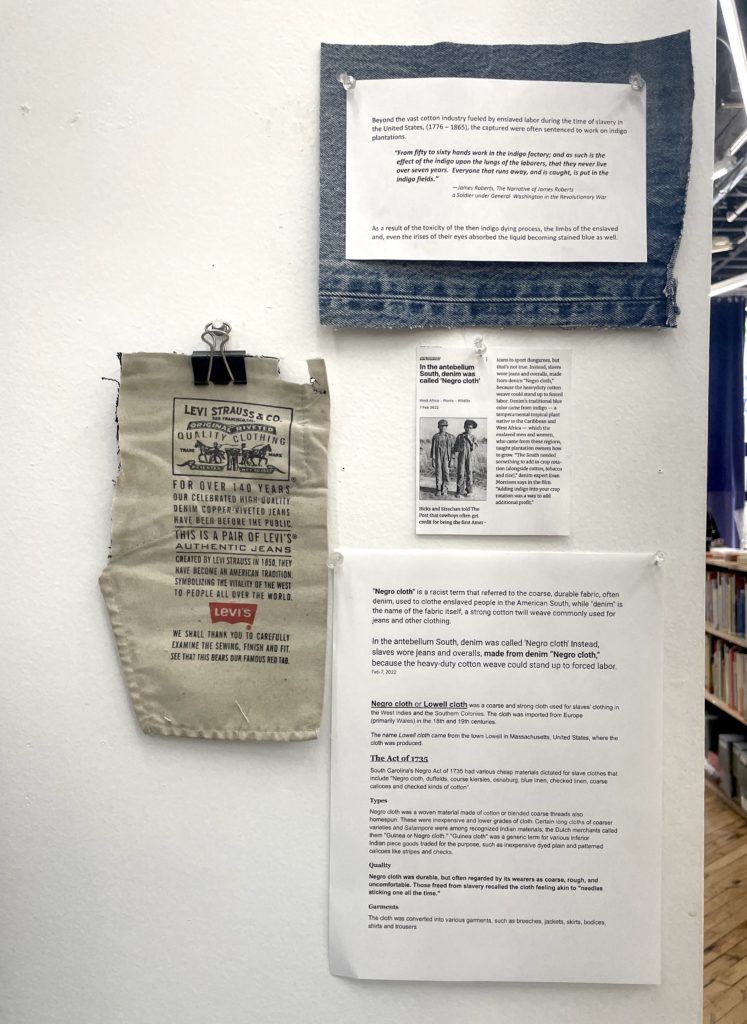

Denim was actually called "Negro cloth", which I found really striking. Deeply racist as per America’s roots, this term and the workwear itself were both designed to be durable in marking people designated only for hard work. As such, it was also intentionally made to be uncomfortable. The fabric was thicker, heavier, and less refined than the cotton or linen clothing made for the UN-enslaved. There are documented accounts from enslaved people describing how the garments would prick and stick them, almost like they were sewn with needles embedded. That discomfort was purposeful. There were even laws in places like South Carolina—1735 and again in 1740—that restricted what enslaved people could wear. If you weren’t wearing that rough cloth, it was suspicious.

So, for me, denim has always represented labor. In the U.S., it's always been workwear. In other countries, it was sometimes used for things like linens, but here, it’s always been tied to labor. That’s why I only use Levi’s denim. Levi Strauss & Co. started around 1863, just before the end of slavery in 1865. It rose with the Gold Rush and became foundational, both industrially and culturally.

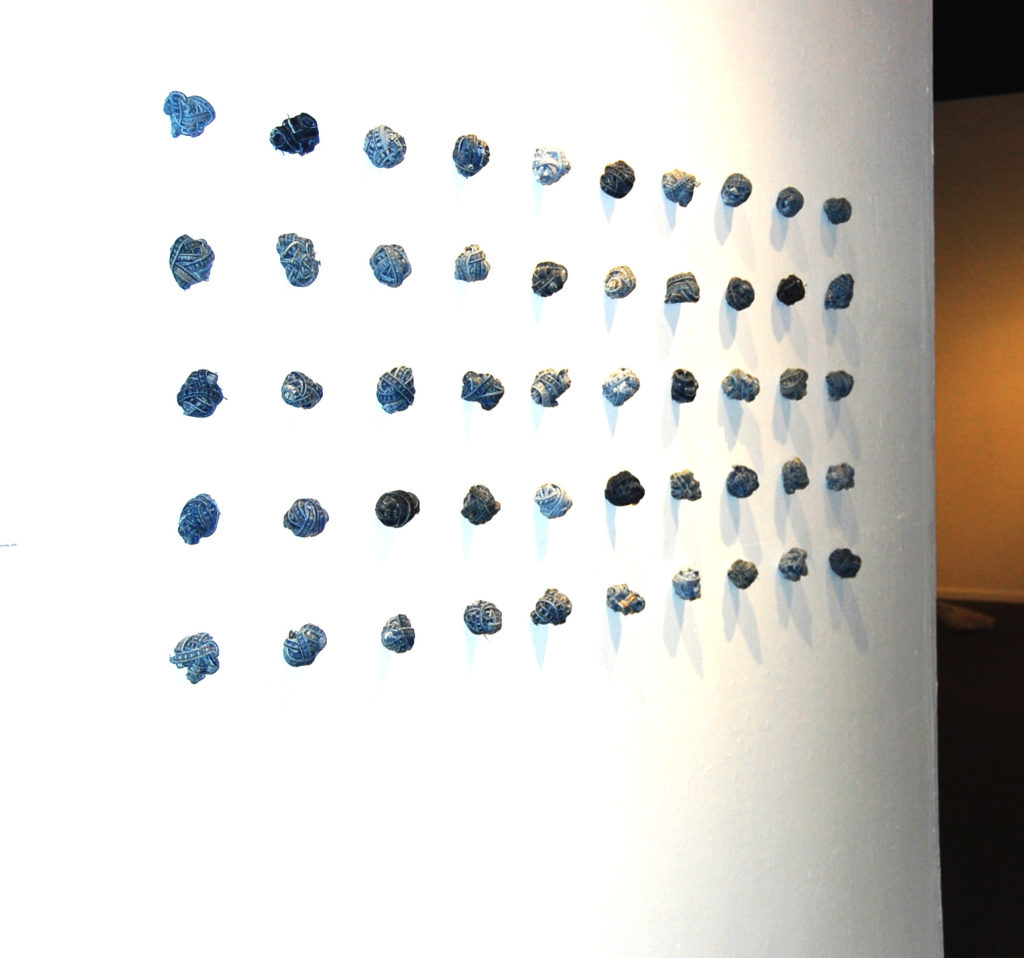

Working with Levi’s connects me back to that time, but also to all the eras between then and now— to fields, factories, seamstresses, railroads. I started using denim around 2005, almost 20 years ago. One of my early pieces was called 50 Knots, where I made 50 knots out of inseams and arranged them in rows—like cotton rows, assembly lines, and cubicles. It was a commentary about how denim, at various times, has always been worn for work. Now, no matter the work, workers continue to struggle at various levels— and everyone is wearing jeans.

That’s when the work started becoming more political, while still rooted in the historical thread. It’s about the evolution: what it was then, what it is now. Denim unites us. During the Civil Rights Movement, it was even worn to show solidarity with laborers and to visually level the playing field.

Denim was also used to "neutralize" women’s bodies, to downplay femininity and become more of a “neutral” human presence, though, of course, objectification still happened (and happens). The idea of becoming less visible as a gendered body was part of it.

As an African American woman, I'm especially sensitive to those dynamics. From being a minority growing up in Minnesota, then as a teenager in the suburbs of New York with more diversity, and as a New Yorker since college, diversity and understanding its value matter to me. Denim's multicultural history is an important example that reflects the roots of America’s struggles.

From a corporate angle, Levi’s chose to make a product that would be innovative, consistent and high-quality. That appeals to me. Levi’s just wear differently. Even when they didn’t cut women’s jeans for curves, my mom would tailor mine to fit. Later on, it became fashionable to let them hang low. Denim really reflects American culture—labor, politics, music, and much is based in and on the Black experience that includes field hollers to blues, jazz, rock and roll, then much later rap and hip-hop. Also, when people were smuggling Levi’s into Russia in the 1950s and 60s, and how denim became an American symbol, iconized first by movies, then popular hippie culture.

And for me, specifically, Levi’s represents the identity of this country—nostalgic, flawed, layered, resilient. I don’t love the word "brand," but even though the first cowboys were Black enslaved men, Levi’s has definitely branded America. If we were a country that would fully acknowledge and own our past, we could make huge progress. Instead, we’re regressing in many ways, and denim—its history, its changes—reflects that too.

And in your process, you cut everything apart and reassemble it. Is that symbolic, or more practical?

I start by removing hems, then inseams, belt loops, and waistbands. I used to fully dissect everything, but now I’m more selective. Sometimes I want to keep the back pocket on for a piece—other times, I remove it. It depends on what I need. Dissecting requires a different mindset than creating, so I’ll sometimes do it while watching TV, just to build up material.

I’ve learned how different styles and materials behave. For instance, outer seams are ribbon-like, while inner seams can be bulkier. The differences affect how things twist or knot. One of my early sculptural pieces was a cluster of pods made entirely of button flies—just to see what that would look like, I took them apart and reassembled them. The insides, the fading, the sun exposure—it all makes the fabric look fossilized. I fell in love with that visual history embedded in every pair.

That visual of denim as a kind of fossil is beautiful. The history is literally in the fabric.

Exactly. The way denim fades, stretches, and softens with wear—it's like a timeline. Some pairs are stiffer, some softer from the start. It all affects how I work with it. The weave, the spandex, the weight—it teaches me something new each time.

And, in reaching back to the time of slavery, there was already a lot that was never taught, shared, or cared about, so I have strong feelings about an administration so intent on trying to erase the past. For me, it really is about holding that thread from the past forward and being able to see it.

With my paintings, it was thin layers, so you could always see the underlayer of the color. It’s like the residue of what always was—it’s there, and it colors the future and the present. In this case, too, my ancestors and the ancestors in this country, Native Americans, also enslaved after genocide and stolen land, are relevant layers of American history. It’s in the nature, the soil, the crops, all of the things, all the pieces, the time, and the effort that exists now because it existed then in the underpainting—it’s important.

That said, my work is not to dwell on the darkness of the past, but to acknowledge it and honor the resilient fabric of a people who found ways to survive, celebrate, persevere, build themselves up and be joyful enough to live, create music, art, dance, and a culture that I am proud of.

I think that’s part of why I love working with my hands. Our original tools are our hands and fingers. Twisting your fingers and wrists with dexterity to reach, harvest, and make things has an old-school feel that to me is a satisfying connection to those who came before.

Tell me about the workshop you're hosting at Textile Arts Center.

The workshop is going to be part hands-on, where everybody will have a pair of denim jeans, and we'll dissect them together. We'll share denim stories, like memories of their first pair of jeans. We’ll be taking jeans apart, and part of the reason I want to have people dissect is to understand my process, but also we'll talk a bit about the act of making and how, back in the day, there were seamstresses actually doing this handwork. Now it's a factory, but there are people running the factory, and there's an effort that goes into making, but there's also a lot of effort that goes into taking things apart. So they'll get to feel what that's like, and it's not easy. You have to pay attention or you’ll stick your finger trying to take things apart. (I do it all the time.) Then, I'll do a mini artist talk, taking people through my work and investigating the pieces of the actual garment and what I was doing with those pieces to figure out what language and shapes I could make with them, and then how that turned into these works.

Teri Gandy-Richardson identifies as an abstract painter, and uses denim as her medium to create work in 2- and 3-dimensions. Her artwork has been shown nationally and internationally. Most recent group exhibitions include Ancestors in Progress II, 2025 at the Textile Arts Center, Brooklyn, New York; The Brooklyn Artists Exhibition 2024-2025 at the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York and Afro Latinx Mix Tape 2024 at the Jamaica Arts Center, Queens, New York. Internationally, she participated in the group exhibition, DENIM— Stylish, Practical, Timeless Blue Fabric with A History, 2020-2021 at the Spielzeug Welten Museum in Basel Switzerland. Originally an Architecture major at The Cooper Union, Teri changed majors and instead graduated earning her BFA in Painting. Teri currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.