WIP Artist Highlight: Isa Rodrigues

Isa Rodrigues sits at the desk in her studio at TAC, working on a small net that she knots over and over again. Behind her are screen-printed nets, layered over each other on the wall. There are prints of nets, too.

Nets.

Isa tells me that her creative practice is as an artist, textile fabricator, and educator. She was a founding member of TAC and develops much of her work at TAC and in community spaces.

“I started learning about textile work from my grandmothers - embroidery, knitting, crochet. Right away I felt a connection, I liked how the motions felt in my hands, and in my body. I studied textile conservation, and though I don’t work in that field now, the way I think about textiles is very rooted in materiality studies. And on the idea that textiles can hold stories and that there's this interdependence between the maker, the environment, the social-political context, and that it all gets archived into the textile. That's something I think a lot about, textiles as archives, like a material memory. In my work, I explore how textiles can be archives of our emotional and physical experiences of the world around us.”

Archive.

I ask her about the dynamic of being an educator and how that has shaped the way she approaches textiles now.

“ Becoming an educator happened very organically. I started teaching when I joined the team at TAC, initially driven by wanting to be part of a creative community in NYC. But through the experience of teaching and developing the TAC project, I started to gain an understanding of how craft education is also a means to preserve material culture. If there isn’t experiential knowledge of how something is made, there can’t be a complete appreciation of the labor involved, and its meaning and value. I also find excitement on how the knowledge of materials, traditional techniques, and processes, can unlock innovation and creativity. Anni Albers wrote a lot about this idea of listening to the material properties and potential, instead of forcing the material to be something else. When I teach, I'm believer in fostering students to get to know their tools and explore the possibilities, but then find what feels right to themselves, their practice, and their vision. After all, textile craft has been practiced for thousands of years across cultures, and so different techniques have been developed depending on the resources available. I learn so much from each student as well, and how they creatively approach the techniques.”

Material.

We talk about textiles as an embodied practice and what drives her materiality exploration in her projects.

“ I’m curious and a lot of times I’m inspired by things I don't understand right away. With net making for example, I grew up around it and saw it being made, but didn’t start to learn it until about three years ago, even though I had been thinking about it. I’m not really sure why, but I think there was a moment I felt like I had to learn it, so I taught myself. And it felt right, and when something feels right to me, on a body level, I tend to stick with it and continue exploring. Like with weaving, for example. I remember when I started to weave that I immediate loved how it felt. It’s a similar feeling to when I’m swimming, like a meditative state. “

Nets.

As we talk about materiality, we transition into the current project she’s working on, and what net-making has looked like so far.

“I grew up by the ocean and that is home to me. It is what I know. A lot of my work explores themes related to the ocean and coastal culture. I think a lot about human interdependence with the ocean and ocean-related natural phenomena, and how there’s a shared language between coastal cultures and the objects, practices, and rituals associated with it.

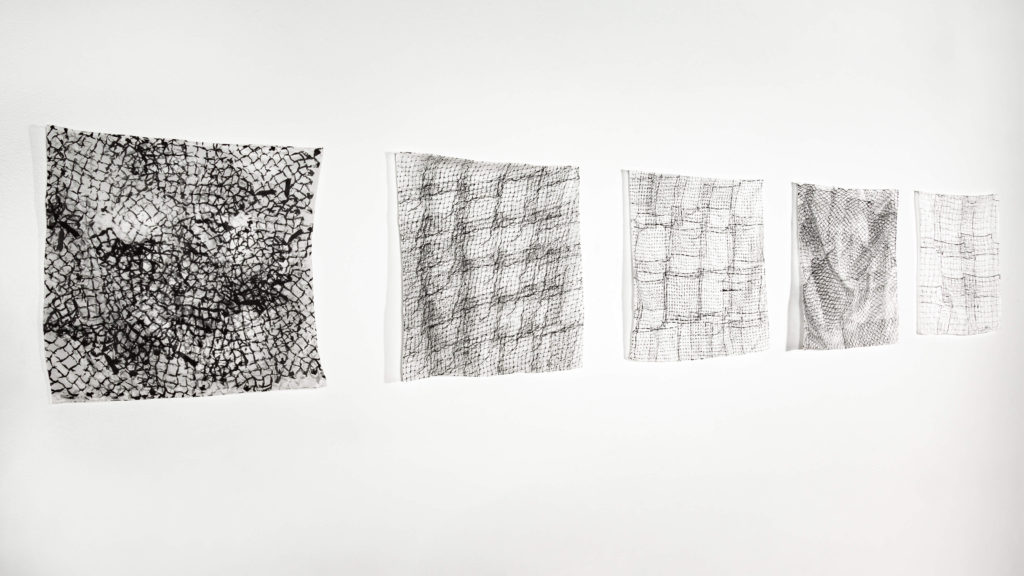

For this residency I wanted to focus on something specific, but that I hadn’t fully explored or resolved yet. I had been thinking about the way a net forms and manifests, from thread to a series of knots, to a two-dimensional form that can then be activated, assuming the shape of whatever it is holding. I’ve also thinking about accumulation, and the duality between visible and invisible. Like when you do see a pile of nets at rest, all tangled and dense, I wanted to capture that feeling of abundance. Making nets takes a long time, so I thought of exploring the idea of accumulation through screen printing. So, I’ve been making nets, burning them into the screen, and making prints and ghost prints on different surfaces and layers.

I didn't really approach the residency with the intention of concluding a body of work, but more to give space for new ideas to develop. Like the workshop for example. I had been thinking about nets and networking (and how they are the same word in portuguese/spanish), and education spaces as a place for people to get to know each other and create community. So I thought that it would be interesting to explore the idea of networking through net-making in the context of a workshop. For net making you need tension, otherwise, the knots don't get tight. So during the workshop participants collaborated in creating tension for each other's nets. And it was so cool so see the space become a net-like installation. And networking happening too, because as you're making the tension for this person that you don't know, you have to talk and connect.”

Ritual.

With her mention of rituals in particular, I ask Isa what they signify in her practice and her own approaches to it.

“In my work, I think about rituals in the context of everyday rituals. Like the ritual of a fisherman going to the ocean, like making the nets, like making food. Ritual as practice and repetition. And I think about the objects associated with it and the emotions associated with it.”

Communal.

We talk about the communal aspect of her practice, and what kind of impact that generates.

“ The community aspect of my practice comes through teaching and through creating spaces, or collaborating in the making of spaces like the Textile Arts Center. These types of making spaces are important, not only because of access to space, but also access to a community of makers, and shared resources. Especially considering how most textile techniques are ancestral knowledge. I’ve also been an organizer and collaborator in different community projects related to growing natural dye gardens in public spaces and sharing resources, like Sewing Seeds, the Textile Dye Garden at Pratt and The Mothership, in Tangier. ”

Research.

Isa calls her research process “chaotic and all-encompassing”.

“Sometimes I will be trying to understand the physics of it other times I will be reading poetry about it. I have deep interest in many disciplines, like science, and anthropology, and my work exists at the intersection of all of it. Especially in my research related to the ocean, my reference is also what I know, and the idea of situated knowledge. So I also collect a lot of research through conversations and oral history, especially when I’m home.”

Document.

I ask Isa about her relationship with documentation and what role it plays in her work.

“I find documentation to be really important. Sometimes I only see the work’s full potential during documentation, by seeing how the work gets activated. I tend to do site-specific documentation, oftentimes bringing the work back to places that inspired it, where the work first started taking shape, and that’s what I’m always most excited about.”

Now what.

We talk about what’s coming up and what she is looking forward to.

“One of the things that I’m excited about, and that I got reminded of during this month, is the importance of creating momentum. I often times have a lot of tabs open and many ideas just existing as sketches, and sometimes that feels enough. But I got reminded of the importance of play and allowing time for process, to unlock new possibilities. And this is the thing I feel like I try to communicate the most to my students, trusting the process, good things take time. And I needed that reminder too. And I’m happy that I allowed that time for play and process during this residency, and excited with all the new paths and ideas for future projects that it opened for me.”

Cover image photo credit: Lynn Hunter