WIP Artist Highlight: Howard Ptaszek

Interview with Howard Ptaszek - Work In Progress

Howard Ptaszek is an experimental Fiber artist living in Brooklyn, NY. His artwork is informed by his love of learning, analysis and synthesis. He has degrees in Physics, Mathematics and Industrial Design. His work reflects his interests in formal properties of materials and processes. He has been weaving since 2009.

Howard is interested in extending the scope of the possibilities of the floor loom, often using new techniques for dressing the loom, adding to the loom itself, or by adding a step (or more) beyond the traditional loom to create his works.

His artwork has been shown in several invitational and juried shows across the US.

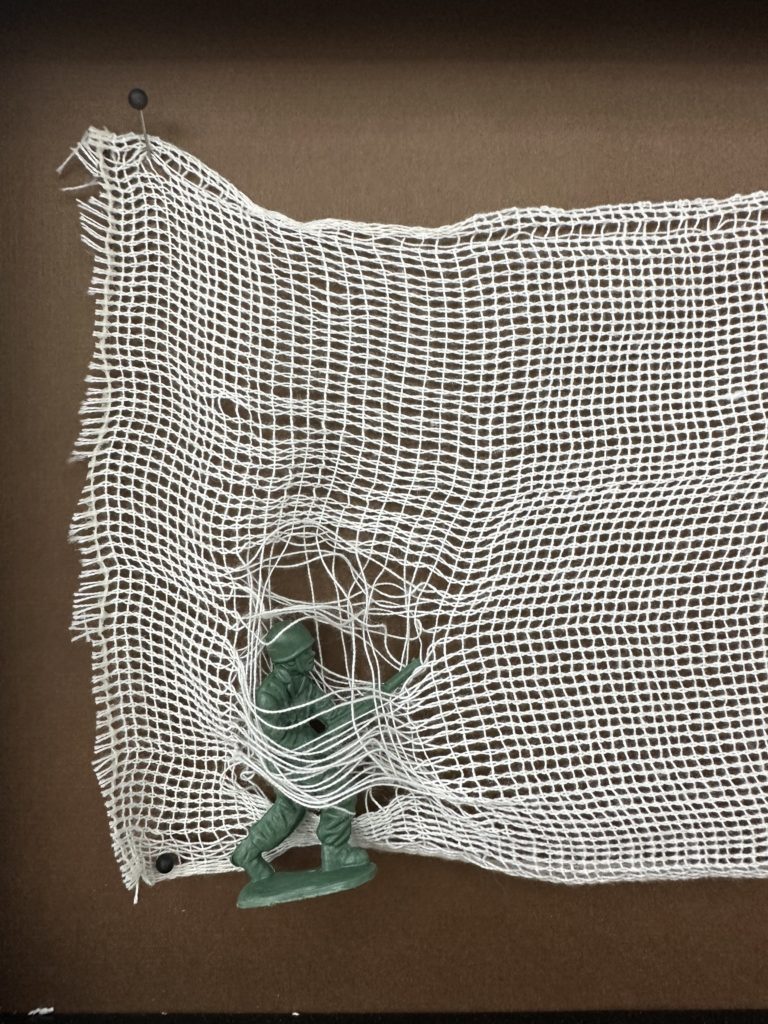

I sit down with Howard Ptaszek in his WIP studio, surrounded by his works of varying degrees. There’s gauze that he wove, with little army men figurines embedded in them. There’s the cube that hangs from the ceiling. There are 100 colors of wool yarn for his current WIP project. As we begin to talk, a staff member comes up and asks about the process of letting someone come into the studio for a tour. Howard says they should reconvene in an hour. He still is the Studio Manager, even as we sit for a conversation.

“This happens regularly,” he says. “We usually give them a tour and invite them into the community.”

But we shift into his work, something he so delicately lays out. We start at a beginning of sorts. He tells me about his education, first in mathematics and physics, and then graduate school in industrial design. He started weaving in 2009 and goes into the mathematical nature of his work, mostly because it always makes its way into his work.

“I make lists and plan out my work in a mathematical sense. But it’s also my way to learn by doing; I try different techniques over the years of weaving.”

Howard talks about the gauze that I was staring at earlier.

“The army men took about a few weeks. The cube on the ceiling took a few months, but they both use the same weave. The timelines and the processes follow each other, in a much more fluid manner over the course of the past 15 years of weaving.”

His works that hang up in the studio space are mostly black, white, and grey, aside from the portrait that stares right into any visitor who comes into the studio.

“Up until the portrait, I mostly worked with black, white, and grey materials. After that I did a piece with 40 different colors, just to do colors. No other reason. Similarly, the piece I’m working on now has 100 different colors.” He points to the shelf behind me that truly does have 100 different colors of wool yarn. “I started going blind from just looking at white and grey, so I moved into color to shock my system, honestly.”

He tells me about his earlier projects, made of rubber and copper, a double weave color piece from yarn off trees.

“I made a progressive pattern with the double weave for the second piece I made.” The mathematical way of the process felt key to this.

He tells me about the pieces he’s done by hand.

“The portrait, for example, I had to make bigger heddles, but when I weaved it, it gave me a blank image. I went back in and wove it by hand. Similarly for the fishing hook one, because the wire couldn’t go through the loom. I find the hand weaving practice to be one of reluctance; if the piece needs it, I’ll do it. That’s the mentality that I go into with every piece.”

I ask him about pieces that have unfinished and if he would like to tap back into them. He chuckles and tells me about a piece he started years ago that is a big mechanical machine that’s supposed to weave air and it needs smoke blown into it to see the actual work.

“I started making the parts for it on a 3D printer and the 3D printer died. So now, I don’t know what to do with that one. I am curious if anyone around here could figure out the 3D printer, but it’s on hold for a while. In the end, the idea is to take something big and clunky that does something delicate. I also have a piece called Water Destruction, where I wove a piece that dissolves under drops of water and I did a video for it. I wanted to do one for all the elements, so I wanted air construction, but that’s on hold. For earth, I was going to grow a garden in a woven piece and for fire, I wanted to do something with fire exploding, but I am a bit skittish about making an explosive.”

We both manage to laugh after talking about the lack of desire to make explosives.

We continue on, into perspectives, and what the influence of community does to a project. I ask him that by spending so much time at TAC, since he is the Studio Manager, and getting to know the different Artist Residents, students, after-school programs, if he is inspired by the mediums and projects that he sees around him.

“Not as much, actually. I think so much of my work is stuck to my own thoughts and ideas and processes that I just want to bring out, and I tend to do my best in that sort of solitary mindset. But I love having the people around me, I need it at this point. The people coming around the studio, the life around, that gets me going about my work. If I were weaving by myself I would go nuts.”

The process, the process, the process.

Howard briefly mentions how the piece he was working on during Covid took all three years of the pandemic, because there was such a constant need to put the work down. I ask him about the impact of pauses in the working period, and how that shapes up differently for each piece

“Usually breaks happen because they have to. For the piece during Covid, I made a special tool to weave it better, but at a certain point, I gave up on the tool and just started using my fingers. At times, it’s also a matter of using a different loom, like learning to use the dobby loom and seeing how existing methods can aid my practice.”

“I end up following a whatever it takes to get done kind of mindset: for the wire piece (he points back to it), if you try to wind wire it twists up, so I had to make a thing that winds it straight. When I didn’t have access to the loom, for example, I made this piece here, which is hand built onto a canvas. I punched holes and put in grommets and figured out the wire needed. It was an obsessive piece, this one.”

I ask him about whether the obsessive nature over pieces and materials still persists.

“Of course, once I see a path towards the work, I just go towards it, and if it changes, I just go through the changed path. It’s stubbornness; I’m more interested in doing the processes I want to do instead of following a strict set of rules.”

We move on to talk about the meaning of working in progress, and what that does to the production and materiality as a whole. He starts by telling me the timing of this process, given that WIP is a month and how he had underestimated it.

“I’m coming in a lot of hours," is the short answer. “Threading the loom has taken 25 hours, and I’ve never heard of that before. There are 8 strands of each color, the pattern which was made mathematically.”

He pulls out the list of color combinations in a set of papers. The pattern keeps going.

“This project for WIP is a simple pattern, but not an obvious pattern. It’s going to have a small pattern that’s meant for two colors, but it’ll mix things up. Two weeks in, and I’m almost done with the warp. For the weft, I’m going to use the same colors in the same order, but they’ll be shorter, so I can pre cut it. I’ll start weaving it, but in the end, everyone wants to see a product, a final piece of sorts.”

I tell him that a warp with 100 colors and calculated combinations sounds brilliant to see.

Continuing with the conversation and transition into color, he tells me about a piece where the order of 8 colors were randomly generated.

“Learning from that piece, I can use those experiences to the one I am working on now.

We jump into materiality, and what influences the uses of certain materials. He tells me that it is usually an idea that he wants to further explore.

“For the EL wire, I wanted to make something that glows, so I found out about EL wire. For Water Destruction, I looked into what yarn would dissolve under water. So I start with an end result and try to get there, and so there is usually a sort of detour.”

I ask him if he can go about a project without too much of an end result. He says he can’t, that he doesn’t know how to go in without patterns.

“Even the project with random colors is such calculated randomness.”

So the question of why weaving comes up, after all this deliberation and calculation.

“I got into weaving because I was looking for something handwoven. It occurred to me that I take for granted that cloth exists, so I saw that I could make something that I take for granted. I learnt glassworking for the same reason; you have a glass and you assume that it has always been glass, but it starts as sand.”

I ask him about his process of documenting his work, and if that shifts his methods in between. He tells me that he’s always been horrible about documentation.

“It doesn’t occur to me when I’m working. It’s always after when I tell myself I should’ve documented. But I also change my steps as I am doing, so I don’t document those either. I don’t think I could start now, it doesn’t make as much sense. Unless someone else takes a picture of me working. If I made a chart of every step, it would be more interesting, but I haven’t cultivated that ability yet.”

So what comes up next?

“Next is hopefully a photographic print, a platinum palladium print, that’s full size. The time spent will be trying to figure out the even tension of the yarn and the specific printing process for the portrait. But I’ll work on something in between; I can’t stare at the same thing forever. It does worry me though, to not know what comes after that. I always have a few ideas ahead each time.”