WIP Artist Highlight: Alejandra Ortíz de Zevallos

Julie Schumacher, Artist Programs intern at TAC, got together with WIP resident Alejandra Ortíz de Zevallos:

How did you come into textiles?

I started to get into textiles when I was studying sculpture in Peru. That's where I did my undergraduate, and I first encountered it as a way of working with recycled materials, specifically plastic bags. I did a big project—it actually started small, but it grew—with a neighborhood community in the surroundings of Lima in a neighborhood called Lomas de Carabayllo. I was working at an art school there, and we developed a project using plastic bags to create a shadow. It was a roof, a pergola in a park that had no shade, and therefore it was not really being used. That was a big outcome after a year of working.

I was trying to get familiar with recycling materials to understand the system we are in—where materials come from and where they end up. And spending time with the plastic, I started to crochet and braid, and I got in contact with a memory that I had from when I was a child, learning from both my grandmas and Tota, the woman who raised me, they taught me those things. So, there was already that memory in my fingers.

As I scaled that process and invited others to weave with me for this big project, I became very aware of how everybody was a weaver. Every mother of the kids we were working with was already a weaver. So, that was the opening for me to become more curious about weavers in Peru in general. I started to travel, talk to people, learn from others, and gather different techniques.

And you were studying sculpture. So, did you transition to textiles, or were you making sculptures with textiles?

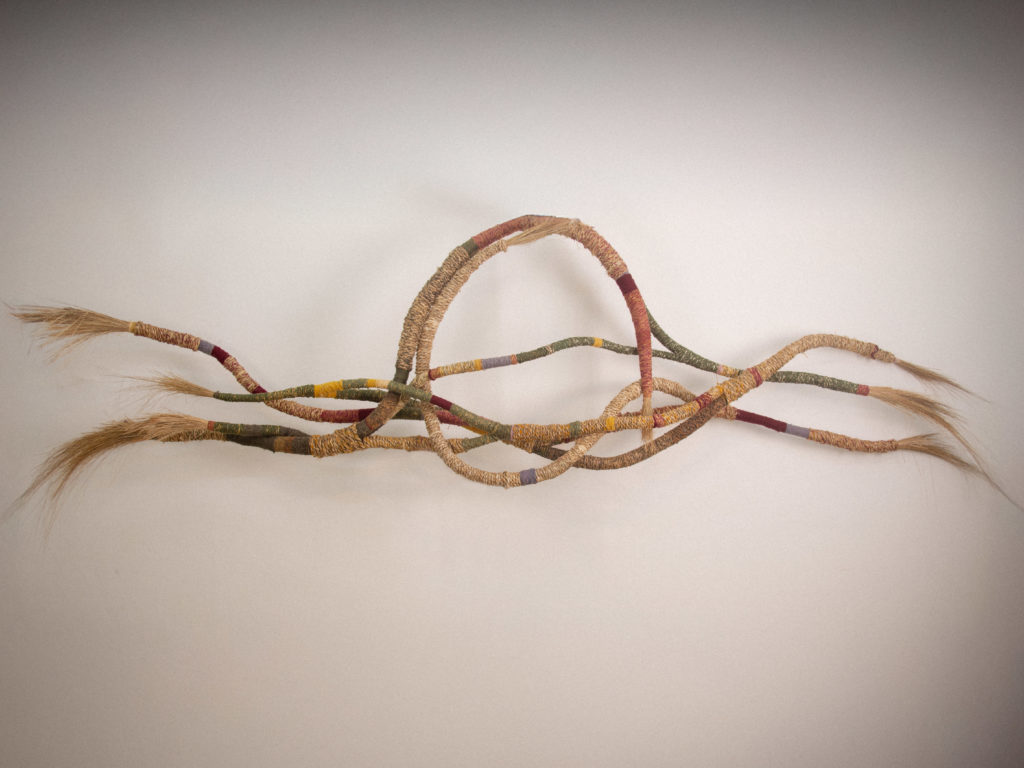

Not right at that moment. Actually, it was a curious process. I was very into creating spaces for relationships. When I was studying sculpture, I spoke with my teachers about whether I could create work with my hands while also inviting others to collaborate with me. And now, looking back, I think that's also weaving—I didn't know it at that moment, but I know it now. I had to go through the discipline of sculpture formation in the sense of going through all the materials that a sculptor passes, like stone and wood. But at the very end, I found myself more familiar with textiles. Now I work with vegetable fibers, which also requires a lot of strength, and at this point in my career, I tend to create big and strong, demanding sculptures. So, I see how my formation has also shaped the way I get in contact with fibers. Also, there are other moments where I look for more delicate processes as a way to compensate and find the shapes and the motives in different mediums.

What is it about the medium of textiles that you feel speaks to you?

It's very intuitive. It's very familiar—it just feels familiar, it feels good, it feels close. But at the same time, it feels like a field where I can grow—there is so much to learn and so much heritage on every land in every place and how all civilizations have craft and their [own] techniques. So, there's always more to learn from it and to configure new ways of abstraction; both in the sophistication of manual process but also in the conceptual knowledge that is embedded in it. So I think that it's a juxtaposition of those two things: the complexity of it and the closeness of it.

You work primarily with vegetable fibers. Do you ever combine them with other fibers, and what is the philosophy behind that?

I look for ways to combine materials that come from different sources—plant sources in some cases, like the ichu (Stipa Ichu) that I have here, which is tall grass. This particular species is brought from Peru, from the Andes, and it grows around 2000 meters above [sea level]. You can also find it lower, but it is commonly found above 2000, and it's in every part of the landscape. It is used for many different purposes, it's very popular for local and domestic uses like for the roofs in houses, forage, and to make bridges, like the Q´eswachaka—it's a very strong fiber with deep history.

I have also worked a long time with carrizo (Phragmites Australis), which is this specific plant that is cast with the ichu because they are part of the Gramineas family, but it's very different, too. While ichu thrives in dry climates, carrizo grows near riverbanks and wetlands. Historically, it has been used for construction, basketry, and musical instruments, among other crafts. Today, it is also used for bioremediation in wetlands. This plant proliferates rapidly due to its root system, which includes stolons. It has spread easily around the world and can be found at elevations up to 2000 meters above sea level. Both are strong and resistant.

And then [I use] yarns—some are cotton, others are alpaca—that I buy from a community of weavers in Cusco. Now, I'm blending them more so they have a mixed composition, and creating a new pallet of color and texture with the other fibers. And sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't. It has a lot to do with the final shape that I am creating and its strength because, in the end, each fiber is like a body—it has different properties. So, sometimes I have to twist one, three times, four times, five times, to march the strength of another fiber. So, I try to find the balance.

How do you source your materials?

It depends. For example, like carrizo and all the sculptures that were made for [my last exhibition], I did the harvest myself. The ichu, I did a harvest for the first time with a community that I'd worked with. But now I purchase from that person—they sell it at the market.

Do you consider environmentalism a component of your work and the materials you use?

Yes, I feel that being conscious of your environment sometimes is beyond the specifics of where you live and more about relationships and how to think about those. For instance, over time, you learn from the material you use, because in order to improve the artwork, you have to spend time with it and listen. That time has the value of a relationship, which is built in trust. And the same with the people. I see the environment as an opportunity to be awake and conscious of what's around you and also what arrives unexpectedly, so that you can learn from it and make something new with that learning that you can pass on. What you do, the conversations you have, and the teachings that you can bring to others.

When you're making work, what are you thinking about?

I think about many things, but it depends. Especially it depends on the situation and the occasion. So, for example, now I am here [at Textile Arts Center], and I am here for a month, and I have what I could fit in my suitcase. So that creates a limit, but that limit also, whether you like it or not, puts you in a creative setting. I kind of like it when there is a specific situation that I have to create a conversation with. So, at first, I tried to think about that. I ask myself, what are the resources that I have available? And I try to sense the space. And then, once I have made some decisions, I try to get on my hands, and that is something very important. I read it for the first time in a book by a weaver, Elvira Espejo, when she said that we are to think with our fingertips, to address that process—and it is real. Now neuroscience has proven how our brain activity improves when working with our hands and how sometimes our bodies know before our head knows, right? So, it is an invitation to take a moment and invest in that way of learning, to just go with your hands and see what directions to take. Then you reflect again—considering different possibilities—but there are also moments when you’re not actively analyzing. Instead, you’re simply creating, making decisions instinctively.