The Local Fiber Movement

In 2011, Rebecca Burgess took on the challenge to only wear garments grown and designed within a 150-mile radius of her home in the Bay Area, California. As Burgess explains in an interview, she wore one outfit for the first six weeks that was sewn from a local rancher’s cotton that had been milled in 1983. Committed to a hyper-local wardrobe, Burgess recalls, “Sometimes I would just be in my house without wearing anything while this one item of clothing was being washed in my bathtub.” Over time, however, local designers, artisans, and farmers worked together to fill her closet with hand-crafted pieces like a bicycle-felted vest, a sweater made from the wool of a 96-year-old sheep rancher, and an alpaca raincoat. Burgess’s campaign sparked conversation and soon grew into a vibrant network of local artisans, makers, and fiber producers interested in reviving the local textile industry.

Inspired by Burgess’s 150-mile-wardrobe, I took to my own closet to do some digging. While thumbing through my hangers and neat stacks of clothes, I began to realize that I had no idea where most of it came from—not only in terms of the fiber or material source, but also the labor, the colors and dyes, as well as the designs. I’m sure you can relate to what followed: a deep dive into the dark recesses of my closet and an extensive purge of my entire wardrobe. After three hours, I found myself sitting on the floor amidst knee-high piles of clothing and paper bags that I would later cast away in a clothing drop-off bin on my way to work (I’m also not sure where these clothes will end up). Here’s the breakdown: out of the thirty-seven shirts I own, only five of them were made in the US. I own one pair of leather shoes from upstate New York. Two pairs of vintage pants. A set of hammered silver hoops I bought at the farmers market. Striped socks from a mill in Alabama. Not surprisingly, these are some of my favorite and most expensive pieces in my closet—my most prized possessions as a 22-year-old, recent college graduate.

Although our clothes may be cheaper than ever before, the ballooning apparel industry comes at no small cost to the environment, producers, and manufacturers around the globe.

Compared to Burgess, my closet stats and purchasing habits are abysmal; not a single piece of clothing (barring the lumpy, too-small hat I knit in sixth grade) is from the 150-miles of my hometown in Northern California. It turns out, however, that I am not so different from my fellow American consumers, who buy on average 70 pieces of clothing per year. The research is quite shocking: today, the average American household spends about 3.5% of its budget on clothing and shoes, less than 2% of which is made in the US. To put this in perspective: in the 1960s, the average American household spent over 10% of its income on clothing and shoes, 95% of which was made in the US.

Although our clothes may be cheaper than ever before, the ballooning apparel industry comes at no small cost to the environment, producers, and manufacturers around the globe. Following big oil, the clothing industry is the second largest polluter in the world and is responsible for some of the most toxic waste sites, groundwater contamination, and greenhouse gas emissions. A quick internet search on this issue reveals a sobering reality of social and environmental harm, waste, and exploitation that undergirds our current fashion industry—the price we must allegedly pay for the clothes on our back. (For a comprehensive overview of this issue, I recommend Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion by Elizabeth Cline, which is available at the NY Public Library).

Responding to such environmental and human rights tragedies like the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh, a large upswell of movements around the globe are challenging fast fashion practices and the apparel industry at large. You may have heard buzzwords like fair-trade, cradle-to-cradle, eco and slow fashion, but here’s another one that you may not have heard before: fibershed. Like the ecological term “watershed,” fibershed refers to your immediate geographical region that supports all components of the textile supply chain—from fiber plants and animals, to mills and manufacturers, to brands and designers. I borrow this term from Burgess who, following her 150-mile-wardrobe campaign, started Fibershed, an organization that seeks to “develop regional and regenerative fiber systems on behalf of independent working producers” by expanding opportunities for carbon farming, regional manufacturing, and renewable energy.

A successful, thriving fibershed relies on consumers as a part of the supply chain that wields great power in terms of the brands and companies that we choose to support. Much like shopping at a farmers market, by giving our dollars to local farmers, producers, and makers who prioritize ecological, fair-trade practices, we reinvest in the health of our community, local economy, and the planet. I find it important to note that these ideas are certainly not new or regionally specific to the West; many around the globe have practiced “local,” environmentally friendly, and low-impact fiber production for hundreds of years. Organizations like Fibershed are simply wielding these ancient, age-old tools and giving us a new vocabulary to fight the fast-fashion industry within a contemporary context.

Much like shopping at a farmers market, by giving our dollars to local farmers, producers, and makers who prioritize ecological, fair-trade practices, we reinvest in the health of our community, local economy, and the planet.

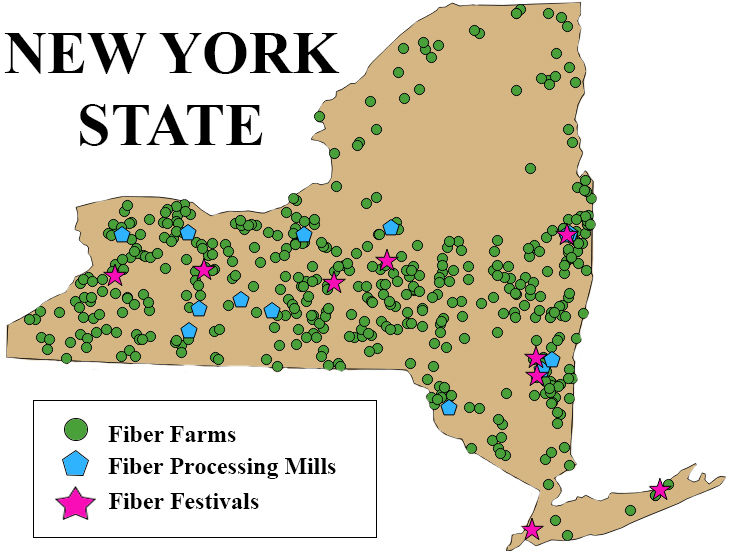

I am greatly inspired by the fibershed movements around the world, however, I think it can also be easy to romanticize this idea of “local” and “small-scale.” I find myself wondering what these trending terms actually mean on the ground for farmers, producers, ranchers, and consumers. I recently sat down with Dana Havas, the admin of Local Fiber, an organization in upstate New York that supports and helps farmers in “solving the infrastructure issues that they face when producing yarn or end fiber products.” As Dana explained, “every part of the supply chain is broken” from the farmer to the mill, weaving company, designer, commercial knitter, and individual consumer. When I asked Dana what she identified as the largest barrier to a thriving local fiber industry, she laughed and simply said, “The problem is our economic structure. We think of large-scale manufacturing as ‘making it,’ which, from the farmers perspective, manifests in terms of cost.” In other words, small-scale, eco-friendly, and handmade can be incredibly costly.

To paint a picture of these daily challenges, Dana described a hypothetical scenario of shipping and processing fiber: “Let's say you ship fifty pounds of wool to Battenkill, Vermont. That’s 200 miles away or so from where we are in New York, which is roughly $150 or more. Turning that wool into yarn is loosely thirty to forty dollars per pound. Processing and washing the wool at a mill is a huge part of the cost. And there is a lag time….you’re not going to get it tomorrow. You’re lucky if you get it in 6 months. And this depends on volume, which can be another problem. Some mills have a minimum volume and even when sending product to mills that don’t have a minimum volume, how much wool you send them will determine how fast they process your fiber.” As Dana spoke, it became clear that similar problems arise for farmers at every step of the supply chain—from finding scouring facilities, to sheering, to accessing markets.

Suddenly, the rosy picture of small-scale, local, and climate-beneficial production gets increasingly more complicated and challenging to realize within an imbalanced economic structure that simply does not prioritize or support these kinds of production. Dana also explained this in how her organization approaches sustainability: “At this point, we are thinking about sustainability in economic terms. I hear farmers say, ‘I have to get rid of my farm because I’m now spending my retirement.’ So although I hope to expand to environmental sustainability in the future, my focus right now is figuring out how to keep farms and mills open.” I walked away from our conversation thinking about the idea of a fibershed in more nuanced and complex ways—that what might be best for the planet might not always best for farmers and producers (at least in the short term). In fact, these two things, a farmer’s livelihood and the health of the ecosystem, might actually be diametrically opposed. The idea that our collective wellbeing and that of the planet are divergent or contradictory, however, is dangerous and reflects a larger, imbalanced economic system.

As the contents of my own closet bemoaned, the issue of cost also arises for consumers like me. Do I really have purchasing power if my paycheck determines which companies I “choose” to support? The limited number of locally-crafted, handmade items in my closet come from a slip in my right-brain tendencies, in which I think, Sure, I’ll trade 10 hours of hard-earned babysitting money on this single shirt. My point is that it can be easy to assign moralistic value to abstract notions of supporting local or buying fair trade. But, in reality, my wallet rules my decisions and nine times out of ten I will opt for the cheaper option if available.

We are already well equipped and armed with the tools to create positive, meaningful change.

I don’t have any answers or conclusive words to offer in the face of such seemingly insurmountable challenges. From my conversation with Dana, however, one thing has become more clear: we are already well equipped and armed with the tools to create positive, meaningful change. Dana’s organization is primarily about sharing wisdom and knowledge, bringing farmers together, and finding collective solutions. In Local Fiber’s quarterly meetings, Dana says she is always shocked by the group’s ability to problem-solve and lift one another: “The people sitting at this roundtable are not just farmers, but also businessmen and scientists and educators. Marcy is also a veterinarian. Anna works in finance and Bob directs a community organization. What they bring to the table is a huge set of knowledge and expertise to strengthen the community and overcome struggles together.”

I think Dana’s wise observation is a big piece of the puzzle: when we actually begin to listen and turn to those around us, we realize our incredible power to provide for one another. While interning at Textile Arts Center the past few months, I have seen the ways in which this organization is guided by a similar ethic and principle of education. Whether learning to patch your jeans, repurpose old clothing, or weave a rug, the process of sharing skills and working with our hands helps us realize our own agency to create, nourish, and fulfill our community’s needs.

Works Cited:

Citranglo, Christie. “A look behind the local fiber movement in Central New York.” Ithica.com. Published December 19,2017. https://www.ithaca.com/entertainment/a-look-behind-the-local-fiber-movement-in-central-new/article_72072ccc-df8d-11e7-91a2-ef09d512e2f1.html

Dirksen, Kirsten. “150 mile wardrobe: local fiber, real color, P2P economy.” Fair Companies. Published September 20, 2011. https://faircompanies.com/videos/150-mile-wardrobe-local-fiber-real-color-p2p-economy/

Vatz, Stephanie. “Why America Stopped Making Its Own Clothes.” KQED. “ Published May 24, 2013. https://www.kqed.org/lowdown/7939/madeinamerica