2024 November Fiber Picks

New York’s prestigious Solomon R. Guggenheim is in-between blockbuster shows, and tickets are half off while the rotunda is closed for installation. But do not let this closure or discounted admission fool you—the exhibition, By Way Of: Material and Motion in the Guggenheim Collection (March 15, 2024–January 12, 2025), is worth a full ticket’s price.

The exhibition culls from the Guggenheim’s permanent collection and takes shape through the recent acquisitions by D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift. Organized by Naomi Beckwith, Deputy Director, and Jennifer and David Stockman Chief Curators, the exhibition spans three floors of the adjacent galleries. The curators used the natural break in flow to their advantage, both highlighting different points of view for each floor while also giving the viewer a chance to digest each floor’s nuanced and conceptual organization. With one foot in art history and another contemplating the contemporary experience—yet always in relation to this art history—I, personally, got a lot out of the thoughtful curation and will try to share some of the highlights as they relate to textiles.

By Way Of introduces the art historical cleavage in tradition that happened in Western Art in the late eighteenth century. Traditional markers of value—materials like paint and marble, and locals like the studio and the academy—were made to make room for a new trend of working en plein air. In other words, artists were going outdoors to work. And while outside, artists captured the ever-changing world around them, the ever-changing public, and the ever-changing public ideals, often using the materials in the world around them as their medium. For many, this led to “refusing academic ideals of beauty and suitable subjects, and establishing the artist as citizen and consumer… .” This shift, throughout the decades and centuries, has allowed for radical ideas and work that reflect how an artist engages with the world, with things in the world, and with the ideas of the world. By Way Of contemplates contemporary art from the 1960s to present through this lens—it “surveys some of the ways in which contemporary artists not only moved away from traditional markers of art practice but also embodied novel ideas of what it means to be in the world.”

The wall label of the top gallery of By Way Of positions the works as “Material as Meaning.” Here, it speaks to the Arte Povera (Poor Art) movement starting in the 1960s—a term coined by critic and Guggenheim curator-at-large Germano Celant in 1967 with two exhibitions and a book cataloging a movement of art and artists disillusioned and neglected by their corrupt governments and responding so by reflecting the industry and instability through their forms and the materials they used. Celant intended the title Arte Povera as a timeless representation of artists across the International art scene, but it quickly became associated with Italian artists from the late 1960s into the 70s. By featuring artists of all ages and from around the world, By Way Of brings Celant’s initial intentions to full fruition.

Materiality is of mind in Shinique Smith’s she waited secretly, between shadow and soul (2021). This installation-meets-sculpture consists of bound clothing and fabrics—sweatpants, polyester fiberfill, ribbon, and yarn. It is hung from the ceiling with two distinct sculptural bulges, one at eye level and one touching the floor, giving a sense of groundedness to the hanging piece. Although the dark colors and knotted materials might offhand suggest a heaviness, there is a thoughtful gentleness in the wrapping of materials and its bulbous plushness. If there is any tension in this work, I feel it comes from this inherent dichotomy.

The middle gallery shows a collection of works labeled “Gargantuan Appetites.” Here the curators wanted to focus on how artists engage with their “beings-in-a-body”—the act of wearing skin, staying alive, feeling safe, the contemplation of identity in relation to government and capitalism.

Mike Kelley’s Riddle of the Sphinx (1991) is a large installation—an oversized crocheted afghan with complementing, gradating colors taking up much of the gallery space. Nine mounds appear sporadically suggesting something is hidden under the afghan—according to the materials list, stainless steel bowls, though their mystery is suggestive to the title. On the wall is a sunset landscape photolithograph of the famous Mount Fuji. Mike Kelley’s conceptual work is often informed by the body’s extreme, and here, where the sunset colors mime the afghan, the work suggests how the afghan, symbolic of care and comfort and protection, might be meaningless in a particular space and offers insubstantial comfort and protection from the elements. Further, “in the same color palette [as the afghan], the print shows the tip of Mount Fuji peaking through the clouds, as if one’s earthbound journey has finally concluded in the afterlife.”

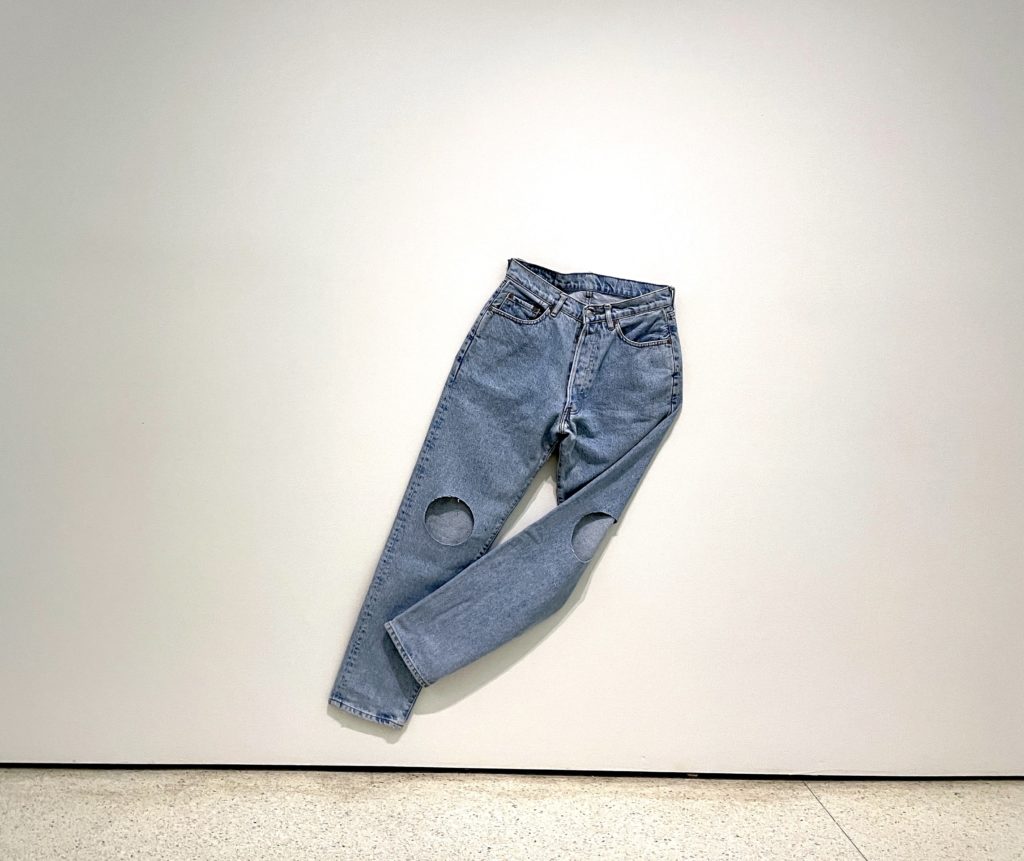

In The Orwell Leg—Trousers for the 21st Century (1984), Joseph Beuys presents a pair of denim jeans with perfectly circular holes cut out at the knees—there is no fraying. Beuys’s work, most simply put, is a “radical collapse of art, politics, and life.” This particular work is a commentary on how one’s identity changes based on how one clothes themselves. Contrary to contemporary fashion, holes in jeans were not a feature of high-minded style in the 1980s as they are considered now (though I’m fairly certain Beuys might’ve dug this evolution in interpretation). Beuys’s holes reference labor and the “citizen-as-worker”—how hard work is so commendable that one’s outward identity is subject to change based on a strong work ethic. Here, with pre-cut holes, Beuys is calling attention to this capitalist ideal by manufacturing this work-ethic identity preemptively and presumptuously.

Anthony Akinbola’s Jubilee (2021), to me, is a show-stopper. The work is a series of semi-shiny strips of gridded fabric, each with a edging that mimics ruffling, all in hues of pastels—sherbets and pinks and yellows—stretched across an 8 x 9 ft. wooden panel. Some of the fabrics cascade over the composition, whereas some hang like tassels off the edge of the panels. Jubilee in title is a celebration of African American history, specifically the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Further reflection of Black culture is that the fabric mentioned “is from a collection of durags, tight-fitting scarves or caps that cover the head with a portion of the fabric, the ‘tails,’ hanging down along the neck.” In keeping with the gallery’s theme, Akinbola’s work asks to consider the textile as a means of protection and strength and/or its tenuousness

The bottom gallery in By Way Of speaks to “Artists on the Move.” These works “evoke architecture, urban spaces, or vessels for travel.” Further, through various assemblages, the works here exhibit how it is the artist who moves “across the world as a carrier of history and cultural accumulations in their mind and on their body”—the artworks are an extension of their experience.

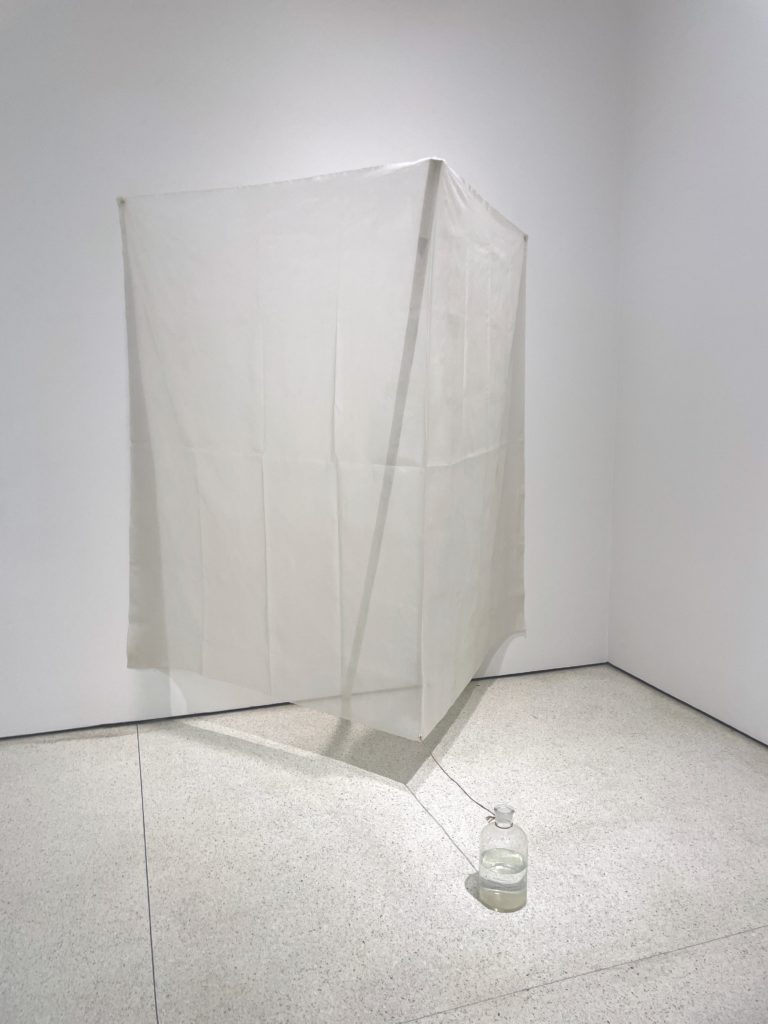

In Robert Rauschenberg’s work Spoke (Jammer) (1976), he assembles a sculpture that echoes the Florida island landscape where he was spending much of his time. A thin, almost paper-like fabric covers a wood pole, sculpted tent-like to the wall. A clear glass jug half-filled with water is tethered to the pole with a rope. Suggestive of an anchored sail, the work gives the sensation of a landscape—the airiness and fragile nature of the materials complementing this sentiment, almost like a scene.

Enclosing the two columns of the bottom gallery is Maro Michalakakos’s Oh! Happy Days (Oh! Les Beaux Jours) (2012)—sculptures of two purple mountains so large that almost nowhere in the gallery do you not see it in your periphery. Further, because the mountains are made with polyester fiberfill, the artwork sheds, so over the course of the exhibition, the corners and walls of the gallery fill up with detritus from the sculpture. Here, the dust that collects is “a monument to the literal and symbolic dust that accumulates around us, evoking the layers of personal and family history found in domestic spaces.” Inspired by her experience growing up and going to estate sales with her father, Michalakakos is keen on the meaning of objects and time. On the subject of time passing, the title is an homage to Samuel Beckett’s 1961 play Happy Days where the two protagonists are buried up to their heads in soil, the mounds are Michalakakos’s reconstructs in bedding material suggesting “a more romantic path through life.”