Learning Kapa

I first encountered kapa, or barkcloth, while walking through the exhibits of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu last November. I was doing an artist residency in glass and had stumbled into the museum to do research into hula, which was part of my project proposal at the time. Seeing kapa, however, sparked something within me that I couldn’t forget.

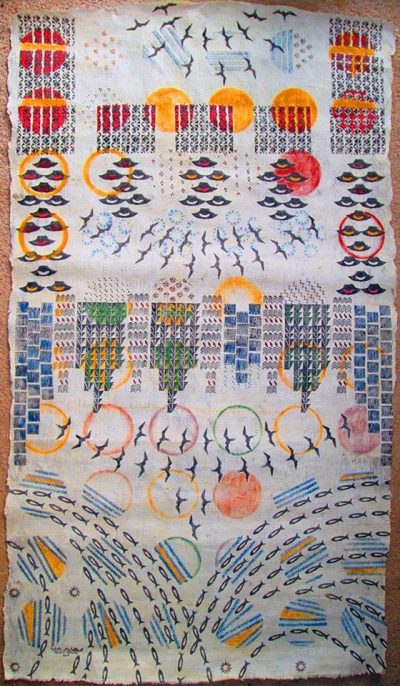

A bolt of kapa on display at the Bishop Museum

The more I read the exhibit descriptions, the more I was astounded by this piece of cloth that hovered between fabric and paper. Through ingenuity and resourcefulness, Polynesian cultures, which lacked plants like cotton or linen to weave from, took the bark of the wauke, or paper mulberry, and pounded, fermented, and dyed it into cloth. In old Hawai’i, kapa was the literal and metaphorical cloth of life. It caught and swaddled newborns, clothed the community as loincloths, skirts, and cloaks, covered sleeping bodies, served as beds, and wrapped the bones of the dead. So, five months later, when I found myself back in O’ahu again, I took this as a chance to learn what I can about the material that bound together Hawaiian life.

My first stop was a group workshop with Dalani Tanahy, a kapa maker of quite a few decades. In the small, Honolulu Museum of Art’s Education classroom, we were welcomed into Dalani’s wealth of passion and knowledge for kapa making. What’s unique to the history of Hawaiian kapa is that it was a lost art for more than a century, smothered by the influx of cheaper cotton fabrics and the West’s political-cultural monopoly during Hawai’i’s annexation. Around 1870, along with kapa making, much of ancient Hawaiian culture and tradition ceased to be practiced. With the loss of kapa making, the once abundant wauke disappeared as well.

Kapa was a lost art for more than a century, smothered by the influx of cheaper cotton fabrics and the West’s political-cultural monopoly during Hawai’i’s annexation.

Thus Dalani, in addition to many kapa makers before her stemming from the Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1960’s, have been reviving kapa through research, self-learning, experimentation, and sharing through workshops like the one I’m taking. Casually commenting how this three hour workshop gives the illusion of kapa making as easy, Dalani talked about her half year to full year long courses, where she leads students to plant their own trees, collect dyes, and pound kapa. This deeply interwoven relationship formed between the kapa maker and the natural materials used lies at the core of much of kapa making, as emblematic of Hawaiian philosophy.

And so, kapa starts with the growing of wauke. The straighter and taller the wauke, the better it is for making kapa. After it grows to a good length (usually takes about a year to 18 months), it’s cut. During the workshop, we each received 12 inch long branches of about 2 inches in diameter. Then, a cowry shell is nestled against the palm of the hand and used as a scrapper, clearing the bark and green outer layers till the white inner bark is revealed. I was pleasantly surprised at how easily the bark came off with the shell, and how soft and light the wood itself feels. Afterwards, we used a shark-toothed tool, called a niho māno, to split the bark and peel it away from the core wood. The strip that faced the inside was a lot smoother and had some residue wetness, and that was the side we folded, facing out.

A niho māno slicing open the bark (Source)

What makes Hawaiian kapa special, as barkcloth is widespread in Polynesia (known as siapo in Samoa and tapa in Tonga) is how soft and light it feels. Touching some of the pieces Dalani brought from her own personal collection, I couldn’t help but think it was worn leather. Dalani joked that the malo, or long loincloth for men, had to, of course, be prepared extra well to give comfort to its wearer. Even more incredibly, kapa was able to be made waterproof through its preparation, withstanding the effects of both salt and freshwater. What really makes Hawaiian kapa unique, however, is in its use of watermarks. By holding kapa pieces in the light, one can see designs made from the grooves of the beaters, which act as signatures. Thus, one can tell who beat a certain kapa by the watermakings of the piece.

What really makes Hawaiian kapa unique, however, is in its use of watermarks. By holding kapa pieces in the light, one can see designs made from the grooves of the beaters, which act as signatures.

Now is when the pounding starts. The first round of pounding is done on smooth, flat rocks called kuo pōhaku, with wooden beaters called hohoa. Kapa is usually made to be pāʻū, a wrap-around skirt for the women, or a malo, a long loincloth for the men. Because this is a three-hour workshop, we only pounded our strips out for one round. But usually, these strips, called mo’o mo’o, would then be dried and can be stored indefinitely. When the kapa maker is ready to make a piece, these strips are put into saltwater solutions to ferment, making them softer and easier to be pounded out. The second round of pounding is thus done with i’e kuku, a four-sided wooden beater with varying grooves that help continue to spread out the kapa. Lastly, the kapa is printed with natural dyes, either through direct application or with bamboo carved stamps called ‘ohe kāpala.

A collection of kapa tools: kuo pōhaku (upper left), a hohoa beating on a wooden anvil, kua laʻau (upper right), and an i’e kuku beater at rest (bottom). (Source)

The day before I left, I took a visit to Ka’ala Farms, where Eric Enos, another kapa maker and farmer, welcomed me in. Stepping out of his pickup truck, I stood breathless. The rolling clouds over Mount Ka’ala, the trilling of birds mingling with the rustling of trees, I felt myself expanding as I breathed in the rich, clear air. Eric then invited me to join in on a fibers workshop for youth led by Mango, an incredibly knowledgeable and kind teacher. Not only did Mango walk us around the farm and pointed out the different uses of various plants for mats, nets, clothing, but we even planted a few more to add to the farm’s collection of indigenous plants.

Mango then took us to the wauke plot on the farm, where a small cluster of trees stood proudly in the sun. As we took in their rustling leaves, Mango excitedly shared the mythical origins of the first wauke tree, a man trying to save his family from debt. He knew and feared the gods’ fury should his family fail to pay, and thus instructed his wife and daughters to plant him by the water. Whatever sprouted, he told them, they should take the skin and pound it until it became something useful. And thus wauke and kapa both came into being. Afterwards, Mango shared all the different types of dyes he had made and collected from berries, nuts, roots, clay, and flowers. What a delight it was to paint with such a wealth of color, all found in O’ahu!

I am so thankful for the overwhelming generosity, care, and community from the kapa makers I’ve met. I came back with a sense of how truly cloth, care, and making are all integral elements in building and sustaining community. Wauke thrive under the hand of the kapa maker, who pays respect through their loving craft in pounding out the fabric that envelops their communities. Through this kapa journey, I have gained not just appreciation for the intertwined relationship between the kapa maker and their natural materials, but also the fearless passion of these kapa makers to honor both tradition and experimentation.

Bibliography

Ka Hana Kapa, Hawai'i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, link.

Hindin, Nikau. “Sept 25.” Kapa to Tapa, 25 Sept. 2018, link.

“Hulia ʻAno: Inspired Patterns.” Bishop Museum, link.

“Kapa Making and Processing.” Kapa Hawai'i, link.

“Kapa-Maker Tanahy Selected as Inaugural Master Kumu for Hawaiian-Pacific Studies Program.” E Kamakani Hou, 29 Mar. 2018, link.