Hiding in the Light

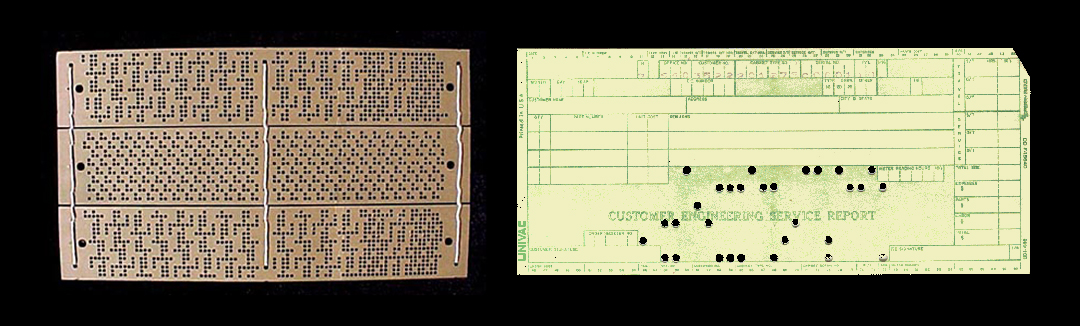

Clandestine information practices and forms of resistance through textiles have a long, shared history. Taking advantage of society’s attitude that women’s work is “low” or “unintellectual,” the wielders of needle and thread have been masters of steganography, or the practice of concealing messages in plain sight. The reach of textiles even stretches into the very information systems we are currently embedded in, with the first computer utilizing a mechanism, the punch card, taken from the Jacquard loom. By acknowledging and owning the roles that textiles, and thus women, have played on the development of our digital world, how can we reclaim, subvert, and decentralize these information structures for collective liberation? As we look at those making work at the digital fringes, it turns out that cyberspace isn’t so untouchable after all.

In her article The Weavers and Their Information Webs: Steganography in the Textile Arts that inspired this post, Susan Kuchera writes, “Information can be used to code textile production, but textiles can also be used to encode information.” A notable and highly contested example, Underground Railroad quilts were thought to have contained specific patterns, like log cabins, monkey wrenches, and wagon wheels, that served as mnemonic and visual maps for escaping slaves. Other patterns were believed to signal “safe houses” along the route.

Information can be used to code textile production, but textiles can also be used to encode information.

Similarly, knitting, with its purl and knit stitches, lends itself easily to encoding. The Belgian Resistance during WW II recruited old women who had windows overlooking the railroad lines, noting the types of passing German trains by a purl or dropped stitch. Other spies translated patterns into morse code, either presented visually or hidden until the piece is unraveled. During WW II, the Office of Censorship even banned the mailing of knitting patterns overseas, revealing the powerful potential of “women’s work” based languages.

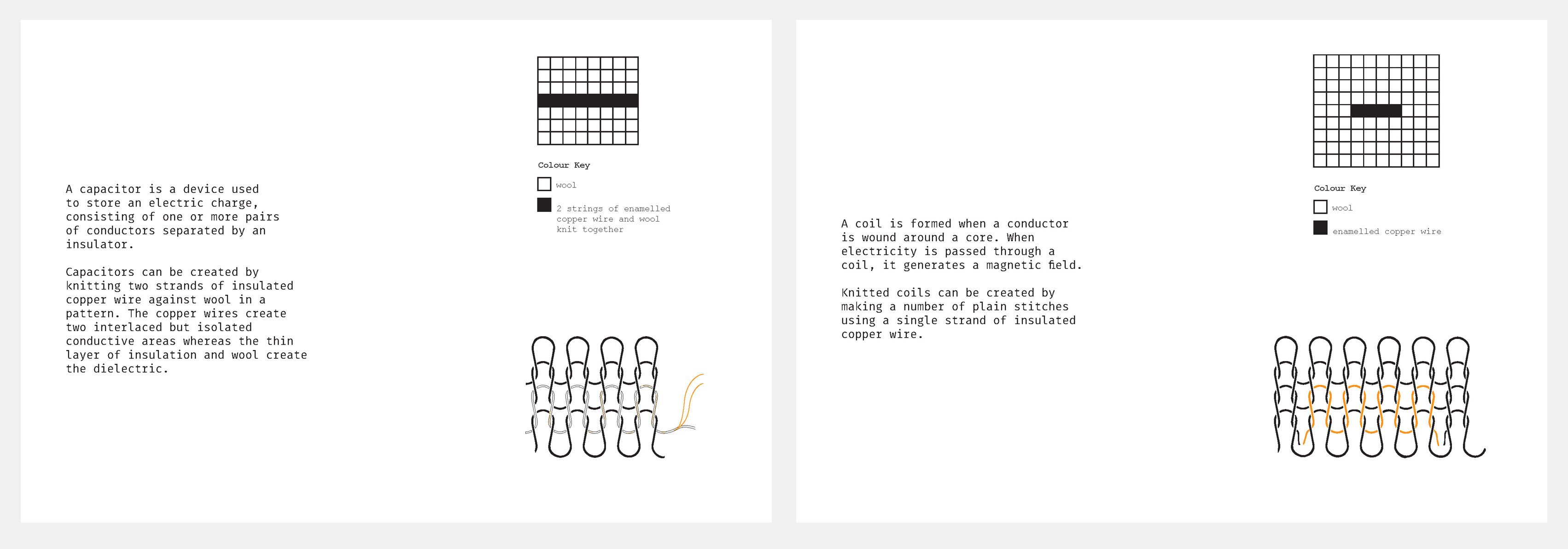

Following along this history, Ebru Kurback, in collaboration with Irene Posch, created The Knitted Radio, a sweater that itself is a transmitter of information, namely FM radio waves. Dedicated to the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Taksim Square, The Knitted Radio is intended to “inspire local, free communication structures” through the individual’s personalization of electronic space. The sweater can connect to an audio source or microphone, and can be heard by anyone tuning to the right radio frequency within a 6 meter radius. As part of their ongoing investigation of using traditional textile techniques to create electronic components from scratch, this sweater is knitted from wool, insulated copper wire, and core-spun yarn with resistive stainless steel. They are all readily available, off-the-shelf materials, making this piece accessible to anyone with the pattern. In this light, knitting itself is 3D printing, and patterns are code.

Through their joint reimagining of electronics through textile techniques, Kurback and Posch ask, “What if craftspeople created the electronics we know? Who becomes more powerful? What materials become important, and who is able to fix them?” These inquiries reveal how inherently malleable information systems are, for materials lie at the origins of how we interface and store the “formless” digital world. Additionally, by recognizing the hierarchy of labor and knowledge tied to the maintenance of our information systems, this awareness offers a space for challenge. We do not have to be reliant on the existing systems for disseminating and receiving information. Rather, we can create our own.

What if craftspeople created the electronics we know? Who becomes more powerful? What materials become important, and who is able to fix them?

In the context of protest and public dissent, this sweater is inconspicuously mundane, and once the transistor, battery, and audio source are detached, it becomes electronically undetectable. The patterns themselves function as camouflage of the everyday, mimicking streetwear that could very well come from retailers like H&M, Gap, Banana Republic, etc. It resides in this liminal space of branded identity, where patterns are chosen solely for decoration, and encoded identity, where patterns reveal complex layers of information about the wearer, but only to those with the decryption codes.

But what if the decryptors have now become non-human? In our current time of hyper surveillance, our identities are now being parsed, decoded, and traded by machines, with black and brown bodies especially captured within the digital gaze. Arising from the political climate of 2017, the all-female Hyphen-Lab’s NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism (NSAF) project tackled security, visibility, and privacy as relating to black women and black communities, utilizing technological applications within product design, virtual reality, and social-psychological/cognitive impact/biometric/fMRI research. The counter-surveillance pattern, HyperFace, emerged as a resulting collaboration between Hyphen Labs members and artist Adam Harvey within NSAF.

noses and mouths to confuse facial recognition algorithms. BBC

Taking advantage of the machinic gaze, this textile, when worn, overwhelms facial recognition software by providing about 1,200 possible “faces.” Inspired by false coloration in the animal kingdom, Harvey reimagines camouflage not to obscure personal visibility, but rather “to reduce the confidence score of a true face, by introducing a background comprising false faces.” Through this instance, HyperFace recognizes what the computer vision algorithms want (faces), and by exploiting that desire, renders the algorithm itself useless. As such, this textile pattern bridges the existence of our physical bodies with our virtual simulacra, reasserting the agency we hold over our own identities.

Having traced the lineage of textile and technological steganography, we see that much of their histories are jointly embedded within the cultural and virtual spaces we inhabit. With this knowledge, how then can textiles be recognized not just for its influence on our digital systems, but itself as a tool to reclaim the power of information? I hope this is just another beginning for collective reimagining and making towards the decentralized and equitable systems we want, one stitch, purl, knot, and thread at a time.

Bibliography

Harvey, Adam. “HyperFace.” Adam Harvey, 2017, link.

Jacobs, Bel. “How What You Wear Can Help You Avoid Surveillance.” BBC, BBC, 13 Apr. 2017, link.

Kopplin, John. “An Illustrated History of Computers Part 2.” Computer Science Lab, 2002, link.

Kuchera, Susan. “The Weavers and Their Information Webs: Steganography in the Textile Arts.” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, No. 13, 2018, link.

Kurbak, Ebru. “The Knitted Radio .” Ebru Kurbak, 2014, link.

Stukin, Stacie. “Unravelling the Myth of Quilts and the Underground Railroad.” Time, Time Inc., 3 Apr. 2007, link.

Witkowski, Jacqueline. “Knit for Defense, Purl to Control.” InVisible Culture, University of Rochester, 18 Apr. 2015, link.

Zarrelli, Natalie. “The Wartime Spies Who Used Knitting as an Espionage Tool.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 1 June 2017, link.