AIR 16 Feature: Malaika Temba

Ciara McNamara, Artist Programs intern at TAC, got together with current AIR 16 resident Malaika Temba:

Ciara: I am a big fan of your work. I am really looking forward to asking you some questions. Firstly, your work is a unique combination of textile practices, consisting of embroidery and weaving. Did you always gravitate towards practicing textiles? And what led you to combine various textile practices together, as well as your incorporation of painting?

Malaika: I was always drawn to fabrics and patterns, especially since I moved around a lot as a kid. Growing up, I always knew where I was based on the textiles around me; by what people were wearing, but also culturally, I knew which textiles were significant. I began studying textiles in college, and that's where I learned how to weave on a Jacquard loom, which is primarily what I use now.

Ciara: Could you explain what a Jacquard loom is?

Malaika: Sure. Jacquard looms are typically used industrially - for upholstery or interior fabrics - because they’re designed for speed and high output, not necessarily complex design. Though some looms and mills are experimenting more, especially as artists bring new energy to weaving.

The loom I primarily use now has a limited color palette and a narrow range of yarns, and it can be fragile when pushed beyond its usual parameters. Since it’s computerized, you have to be cautious—too much experimentation and it’ll break warp ends, and slow down or even break the machine. I’m also deeply interested in the programming side: creating weave structures that add dimensionality, or simulating effects that are much harder to do manually.

When I incorporate painting, I usually do it over the woven surface. I try to keep the paint thin enough that the woven texture remains visible. It’s not about covering the textile, but extending it.

Ciara: How do you see your work evolving through your medium?

Malaika: I’m always experimenting. Textile work already feels niche to many people, but within it, there’s so much ground to cover. I’m currently working with knitting, felting, embroidery, and silkscreen. Lately, I’ve been especially drawn to silkscreen—there’s a lot I want to explore there in upcoming works.

Ciara: Ooh, I am already looking forward to what will come of that. I am also quite fascinated by the carefully crafted color palettes of each of your artworks, many of which strictly use soft pinks, purples, blues, and greens, and sometimes conversely will only use deeper, richer brown, green, yellow and red. Why are these colors important to their subjects?

Malaika: I’m drawn to colors that look like they have been faded by time or sun—soft, weathered pastels with history. I’m also interested in hues that don’t translate well on screen—those ultra-specific, rich yarn or pigment colors that make your eyes stretch.

With weaving, the palette is constrained by the yarns available, so a lot of the color mixing happens through programming the weave structure—how different colored threads intersect. It’s like layering pencil marks: the threads don’t blend like paint, but they create the illusion of color mixing when viewed from a distance.

Ciara: That reminds me also of how you mix color with colored pencils. You overlap two colors that create the effect of the color they mix to make, without directly mixing those two colors together.

Malaika: Exactly. The threads stay distinct, but their interaction creates something new.

Ciara: When you incorporate painting into your weaving, is it meant to expand the color palette of the artwork itself? What relationship does the paint have to the yarn?

Malaika: Usually yes—it’s a way to extend or push the palette. Sometimes I use very watery paint, almost like a dye, so the pigment sinks into the weave and enhances the texture. I reserve thicker paint for figures, to give them more human detail or to make them pop from the woven surface.

Ciara: Can you tell me how your work addresses globalization and current labor standards in terms of the expectations of women’s labor?

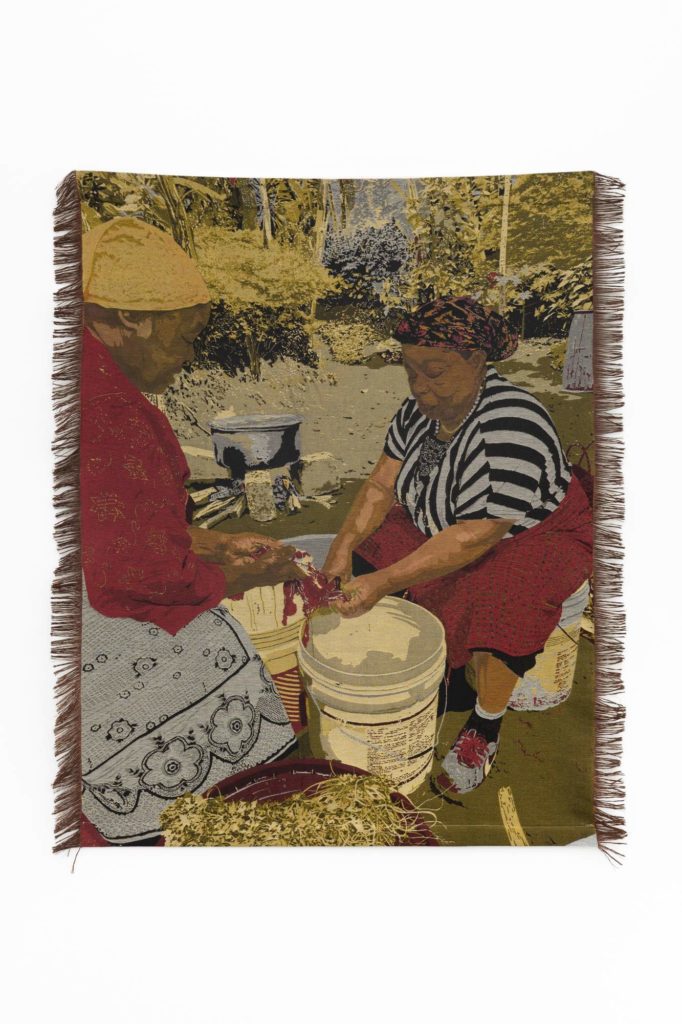

Malaika: Yes, I mean it’s about that, but in a more intimate or familial sense. I’m really interested in labor—physical, emotional, intellectual. Most of my scenes are set in Tanzania, where my family is from, and they often depict women at work. Because in so many ways, women are the backbone of labor there.

So when I use this industrial machine, I’m pushing against its rigidity. I’m inserting softness into something designed for mass production. In that way, it mirrors the duality I experienced growing up: navigating global systems while holding tight to intimate, personal histories. My work becomes a site where those two realities (the industrial and the familial, the mechanical and the handmade) come into conversation.

Ciara: So, in reflecting on your relationship to Tanzania, you currently have a solo exhibition at Gaa Gallery in Cologne, Germany, your first show with the gallery. Can you tell me about the process of creation for all of those works?

Malaika: The show is titled Ni Hivi Hivi Duniani, which is a Tanzanian proverb meaning, “That’s the way things are in the world.” I love proverbs like that, they show up mostly on kangas, Tanzanian printed fabrics worn as garments, used in homes, and with text that could be anything from a blessing to a warning to “Merry Christmas.”

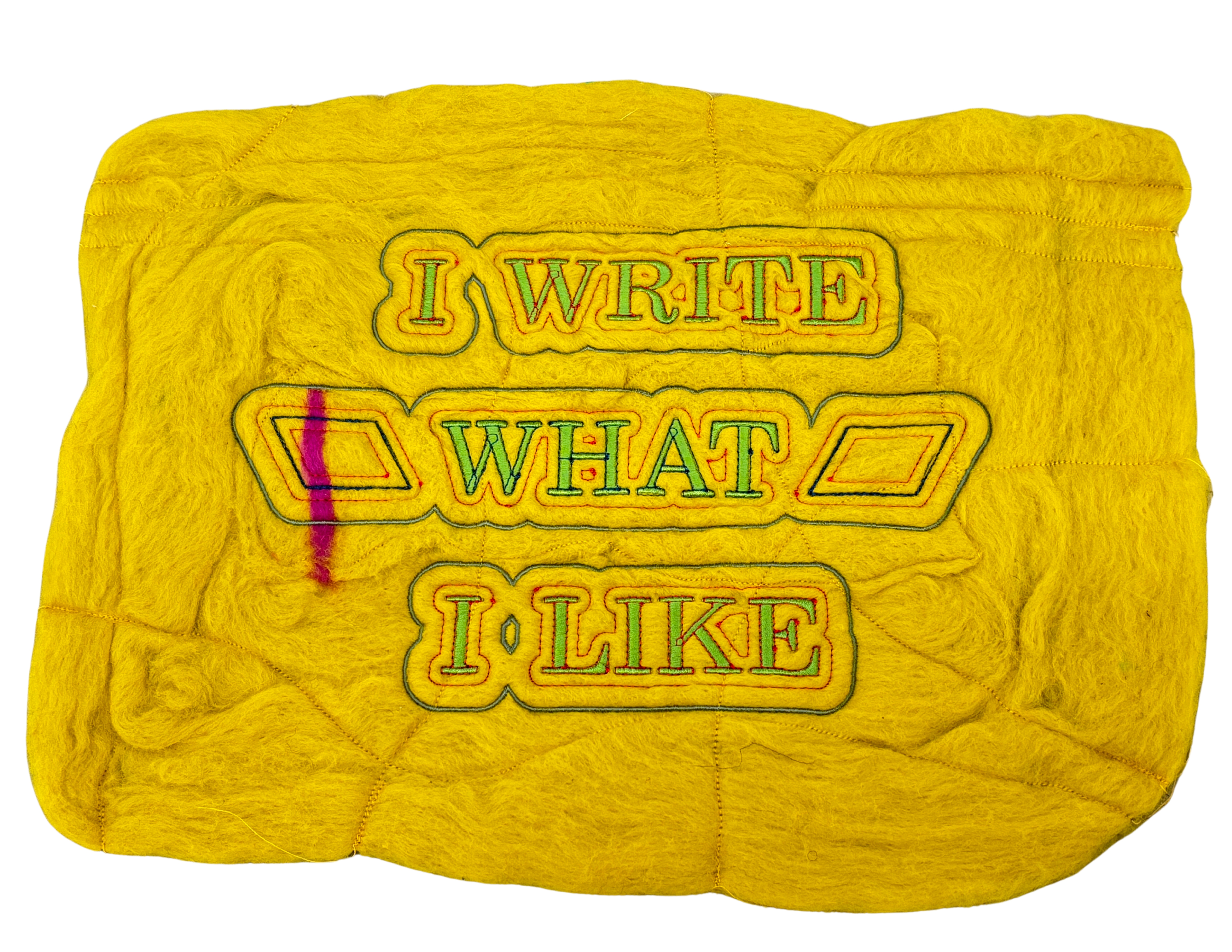

This show is grounded in kangas, both visually and thematically. The works reference their patterns, colors, and text, while also incorporating new embroidered text works - something I’ve done before but am now exploring more fully. A lot of the figurative works depict my aunts resting after long days of work, often rendered in either the soft pastel palette or deeper red-yellow tones. Malaika Temba: Ni Hivi Hivi Duniani (2025)

Ciara: Yeah, the pastel and deep, richer palettes are all alike in their warm tones. Could you speak more about the subject of labor in this show?

Malaika: Labor is a central theme, especially as expressed through hands. Whether preparing food, farming, or cooking—those hands are a site of care and survival. I try to honor that work. The patterns and surface textures in my textiles mirror that effort. The text adds another layer: emotional labor, ritual, community. It’s about recognizing that everyday life—especially women’s labor—deserves reverence. Change is needed, yes, but this work is about recognition first.

Ciara: The artworks that come to mind from the show are the hands in a slight shifting motion, in very neutral, darker colors.

Malaika: Yeah, so in that series, the emphasis is on the motion between the hands. There are five total in the series, and they are sort of like stills of hands in action. In each piece, there is a fringe that unravels depending on the shape of where the hands are positioned, to emphasize the action that the hands are engaged in.

Ciara: Since we are currently moving into the last part of the residency, are there any ideas in your project proposal you could share that you are excited to start working on further?

Malaika: I’m excited to get back into silkscreening! I’ve been weaving so much the past few years, but TAC has a nice dark room and print table so I want to take full advantage of the facilities while I’m here, and after the residency as well!

Malaika Temba (b. 1996, Washington, D.C.) is a Visual Artist based in New York. Temba creates textile works that honor the lineage of the diaspora’s aunties and femmes, addressing the responsibility, time, attention and patience expected of these laborers, comforters, nurturers, and providers. She wields fabric—an oft-overlooked material conflated with gendered notions of softness—as a resilient and unbreakable format to confront labor standards and global trade. Having grown up across Saudi Arabia, Uganda, South Africa, Morocco, and the United States, her lens and creative processes embrace globalization and intercultural connection by shining light on all of its intricacies.

Temba graduated with a BFA in Textiles from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2018. In 2021, she was honored as the recipient of the YoungArts Jorge M. Pérez Award and since then, she has been selected for significant residencies: Art Omi (2023, NY), MASS MoCA (2023, MA), Bandung Residency, MoCADA + A4 Arts Alliance (2023, NY) and Silver Art Projects (2024, NY). Temba has had solo exhibitions with Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami (2021; 2024; Miami, FL), Lilia Ben Salah Gallery (2023; Paris, France), and Gaa Gallery (2023, Cologne, Germany). She has participated in group exhibitions with Allouche Gallery (2021, NY), The Yard (2021, NY) and Mindy Solomon in collaboration with Albertz Benda (2022, LA). Her work has been collected by various public and private collections, including the collections of Jorge M. Pérez and Beth Rudin DeWoody.

About the AIR program:

TAC AIR combines studio access with a rigorous interdisciplinary curriculum, and regular critical dialogue, providing residents an opportunity to learn and explore the textile medium, and an alternative to traditional higher education programs. The residency culminates in a group exhibition produced and hosted by TAC. Since 2010, TAC AIR has graduated over 100 artists and designers whose work continues to further textile art within the fashion, fine arts, design and art education fields.