2025 May Fiber Picks

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstractions

Museum of Modern Art

11 W 53rd Street, New York, NY

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5733

April 20–September 13, 2025

If there were a single medium that could most effectively illustrate the story of modern art and the radical world and social changes that spun out from it, that medium would be textiles. Which is why Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstractions, on view through September 13 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is not only an exquisite and varied exhibition of woven- and woven-adjacent artworks but a fascinating tour of modernism’s history.

Modern art changed the world. Or, was it the other way around—that the world was changing, so art, as a reflection of society, changed too? If the approach to history is unknowable and the history so layered and dimensional that there are endless ways to tell the story, how does one even begin to tackle the topic? Woven Histories could be told a thousand different ways, and the curator, artist Liz Collins, thoughtfully narrowed the scope by telling the story in seven themes in seven galleries. Featuring approximately 150 cross-disciplinary works by nearly 60 artists, the show can be experienced as a textile history lesson or, alternatively, simply as a visual feast.

The first gallery is titled Envisioning a New World. After World War I, dreaming of a better world, many of Europe’s avant-garde artists moved from the canvas and space of galleries toward exploring items of utility and production in mediums like architecture and fibers, which supported their visions of a social utopia. They brought bold, geometric designs to textiles, blending art with everyday life. In Moscow, Constructivist painters swapped brushes for blueprints, designing stylish, functional clothes for the modern Soviet woman. Meanwhile, at Germany’s Bauhaus school, artists turned their focus to creating smart, affordable, industrially made goods. In the weaving workshop, legends like Gunta Stölzl and Anni Albers hand-loomed vibrant fabric swatches and wove stunning wall hangings, merging modern design with the comforts of home.

Line Involvements is the subject of gallery two. After the Bauhaus shut its doors in 1933, its spirit of hands-on, materials-first creativity didn’t fade—it simply unraveled and rewove itself elsewhere. At places like Black Mountain College, the famed experimental school in North Carolina, weaving wasn’t just a craft, but a playground for exploring texture, structure, and meaning. In other words, weaving was art. Artists across the Americas pushed thread beyond the loom, treating it like a drawn line, turning flat hangings into bold fiber sculptures. They looked to ancient textile traditions for inspiration while inventing new forms entirely. At the same time, New York’s avant-garde got tangled up in thread, string, and wire—everyday stuff that twisted sculptural norms into something soft, flexible, and thrillingly offbeat.

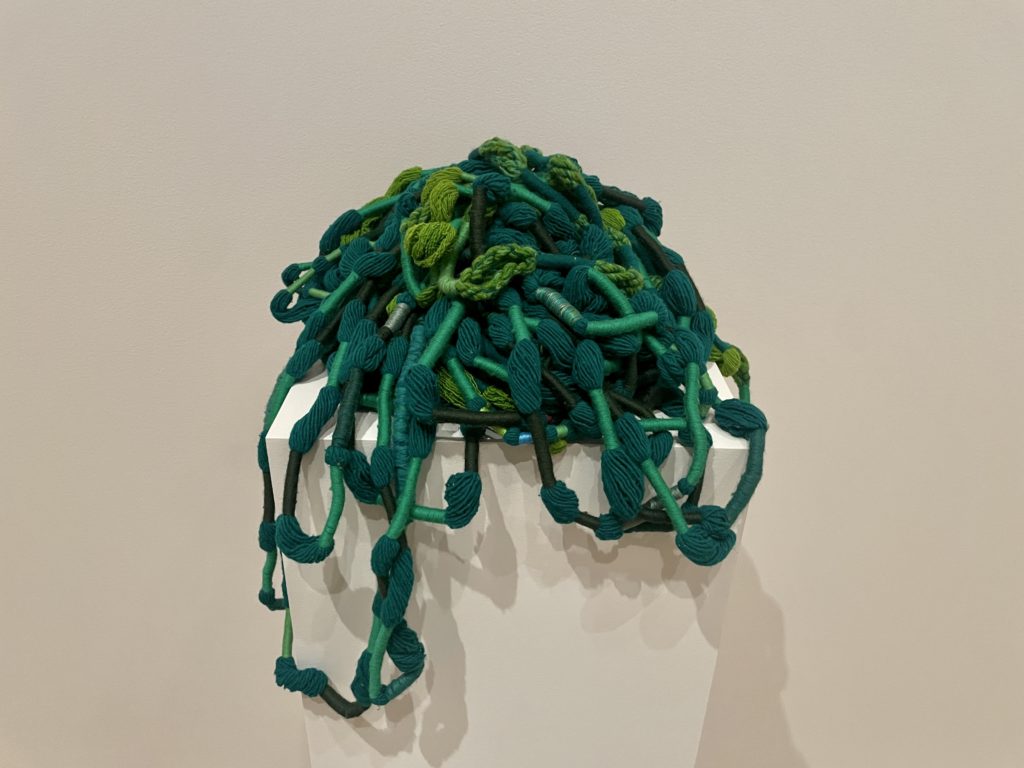

Paintings, drawings, weavings, and sculptures by Kay Sekimachi, Marisa Merz, Agnes Martin, and Olga de Amarall, to name a few, are examples of work in this lineage. By Sheila Hicks, a heaping pile of vibrant threads in variant greens, twisted and wrapped both tight and draping, pours over the edges of a piller its perched. A half-moon in black wrapped threads, utility-looking, yet with no known utility, by Eva Hesse, hanging on a wall, it would be delicate if it weren’t so large, and as a result, it remains mysterious. Rosmarie Trockel’s canvas of warp with no weft is a minimalist masterpiece.

Galvanized steel, brass and iron wire, 26 x 22 x 17" Photo credit: Julie Schumacher

The third gallery explores Grids, Nets, and Knots. Born from the classic over-under dance of warp and weft, the trusty grid was once just the backbone of basic weaving. But postwar fiber artists saw more: a playground of pattern, meaning, and modernist flair. While some painters in the 1970s turned their backs on the grid, others turned to riffing on Celtic knots, Islamic swirls, and slicing up canvas to reveal its woven guts. Some ditched grids entirely for loop-ridden nets and tangled webs. Up until the 1990s, the lines between fibers and fine art were stiff, and many fiber artists working remained outside institutional conversation. Though modernism sought to disrupt traditions around art, nearly a century later, those conversations and thoughts on abstraction had become traditional themselves. Ironically, it was the introduction to digital technologies that shook things up, blurring the boundaries of abstraction and opening minds and space for critical conversations around different technologies, practices, and realms that had been there all along.

This large gallery features works by Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Regina Pilawuk Wilson, Yayoi Kusama, and Alan Shields, to name a few. Ed Rossbach’s tapestry of raffia, titled Tapestry, reconstructs a likely inexpensive deconstructed fiber into a gorgeously wonky braided and woven piece, whereas Ruth Asawa's meticulous wire sculptures almost disappear the hand—both, to me, are opposite examples of perfectly amoebic forms.

Behind every pair of denim pants and decorative pillow is a tale of who made it, how, and what the maker earned versus how much it retailed—in other words: at what cost, financially and socially. Today’s textile industry spins big bucks from low wages, leaning hard on global inequalities. Fast fashion churns out trends, trash, and carbon footprints faster with each passing season. The artists in this gallery examine these concepts. With a mix of materials and methods, they stitch sharp critiques of profit-chasing and point a finger at our own shopping habits. Some also poke holes in the usual “us vs. them” thinking, weaving messier, more thoughtful takes on labor, tradition, and tech.

Labor is the topic of the fourth and smallest gallery, featuring works by Diedrick Brackens, Lisa Oppenheim, and the curator of this exhibition, Liz Collins, to name a few. It also features one of my favorite works in the show, a piece titled Grey Scale I and II by Polly Apfelbaum. The piece is made with marker on synthetic velvet in grids of various pinks, browns, and yellows, almost like skintones. It is delicate but hangs precariously from the wall with hooked pins. In this work, Apfelbaum considers how the “creative leisure” and domestic tradition of quilting have also historically doubled as an invaluable form of supplementary income, calling attention to the blurred lines of pastime and labor.

The fifth gallery speaks to the theme of “Life Wear” and Self-Fashioning. In the shake-it-up decades of the 1960s and 1970s, style wasn’t just about looking cool—fashion was a battle cry. Activists for women’s, queer, and civil rights turned clothes into loudspeakers for identity and values. At the same time, stretchy knits and space-age synthetics took over wardrobes, marking a major textile shift. Fast forward to the mid-1980s, when a new wave of women artists began threading these social and material revolutions into their work. Blurring the lines between fashion and fine art, they stitched together bold critiques of culture through garments that were part armor, part attitude. Influenced by rebellious styles of the past and experimental artists of the early 20th century, their work walks the line between playful and political, never just something to wear.

Artist Ellen Lesperance’s How Does It Feel in Your Chicken Coop, Soldiers? Little Macho Cock-rells Parading the Wire? Strutting in Your Dustbowl, Arid and Treeless, You Obey Orders but We Are Free! (2018) consists of both a hand-knit sweater by the artist and an accompanying drawing on paper of the pattern. In this work, the artist has constructed a garment created by women and worn by them and other activists protesting in anti-nuclear demonstrations. Knitting patterns are inherently abstract—they are codes to utility, patterns to technology, maps for replication, historical documents, and visual objects of beauty. Lesperance’s work intentionally plays with all these concepts.

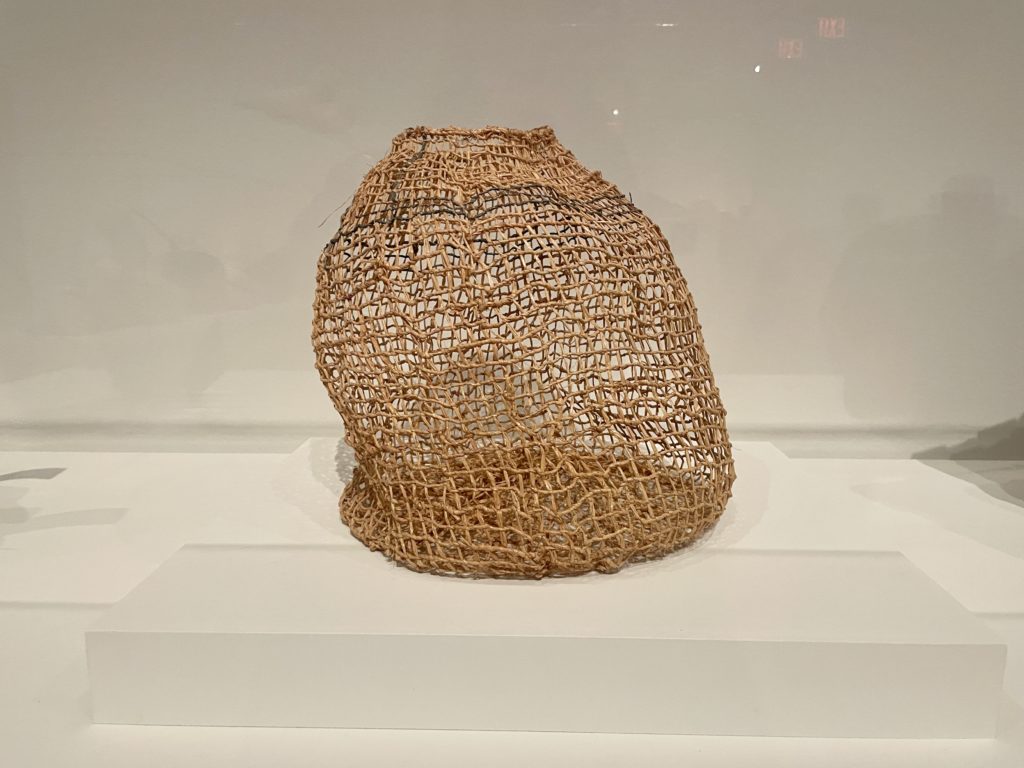

Gallery six is themed Basketry. Baskets rarely get their credit in the art world, but Ed Rossbach—a fiber wizard of the 1960s—challenged that admission. To him, every humble hamper was kin to high art. Around the same time, sculptors with a taste for the handmade ditched chisels for knots and coils, weaving new dreams from old tricks. Elsewhere, especially beyond the West, weaving wonders had always dazzled—like bamboo sorcery in Japan’s tea traditions, which later blossomed into funky, just-for-fun creations. Meanwhile, Indigenous makers across Australia and North America began breathing fresh life into ancient basket spells, twining heritage and pride into every loop. This gallery is teeming with incredibly experimental examples of fiber vessels and baskets—nearly three dozen—by artists including Kay Sekimachi, Katherine Westphal, Yvonne Koolmatrie, Shan Goshorn, and Lillian Elliott, to name a few.

In this seventh gallery, Community and the Politics of Representation, fabric becomes a force for visibility and voice. These garments aren’t just about style—they’re statements, stitched with stories of community, resistance, and identity. Some, like Jeffrey Gibson’s 2019 The Anthropophagic Effect, Garment no. 4, are made for performance but meant to be seen, and honor those often left out of the national narrative. Alongside are tapestries, rugs, and wall hangings that act as soft monuments, holding space for those facing dislocation, loss, or the search for home. The artists draw from a rich blend of influences: ancestral traditions, class and race solidarity, and the bold spirit of queer and feminist thought. Here, textiles don’t whisper—they loudly shout, shimmer, and stand their ground.

In this section appear works by artists that include Analia Saban, Ann Hamilton, Teresa Lanceta, and Marilou Schultz, to name a few. The work by Igshaan Adams’s Vroeglig by die Voordeur—my other favorite new find of the show—with subtle colors and textures from afar, is both dazzling and detailed up close. Invoking the patterns of an oriental rug, Adams, who identifies as queer and Muslim, uses strands and beads to weave and mend, building from thousands and thousands of individual parts a whole. Themes of repair and individuality within community and grander traditions bounce back and forth between inverse themes of wholeness, community, and grander traditions within individuality.