Paola de la Calle, “Entre Azul Y Azul”

DOWNLOAD ENTRE AZUL Y AZUL HERE

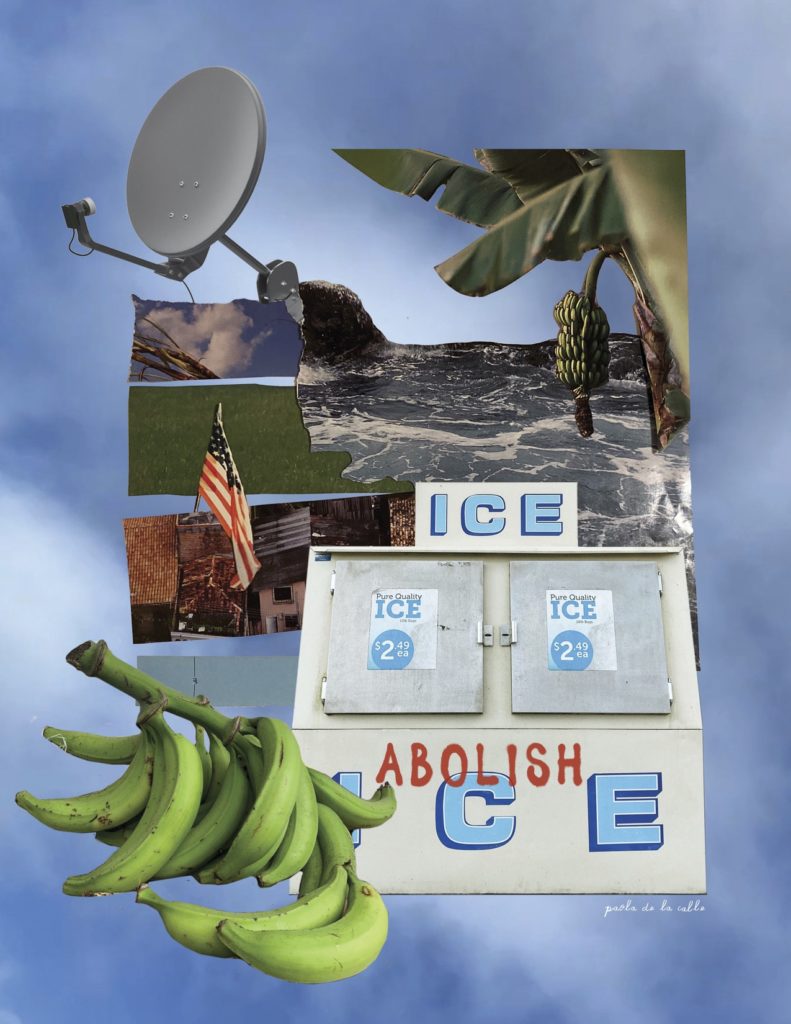

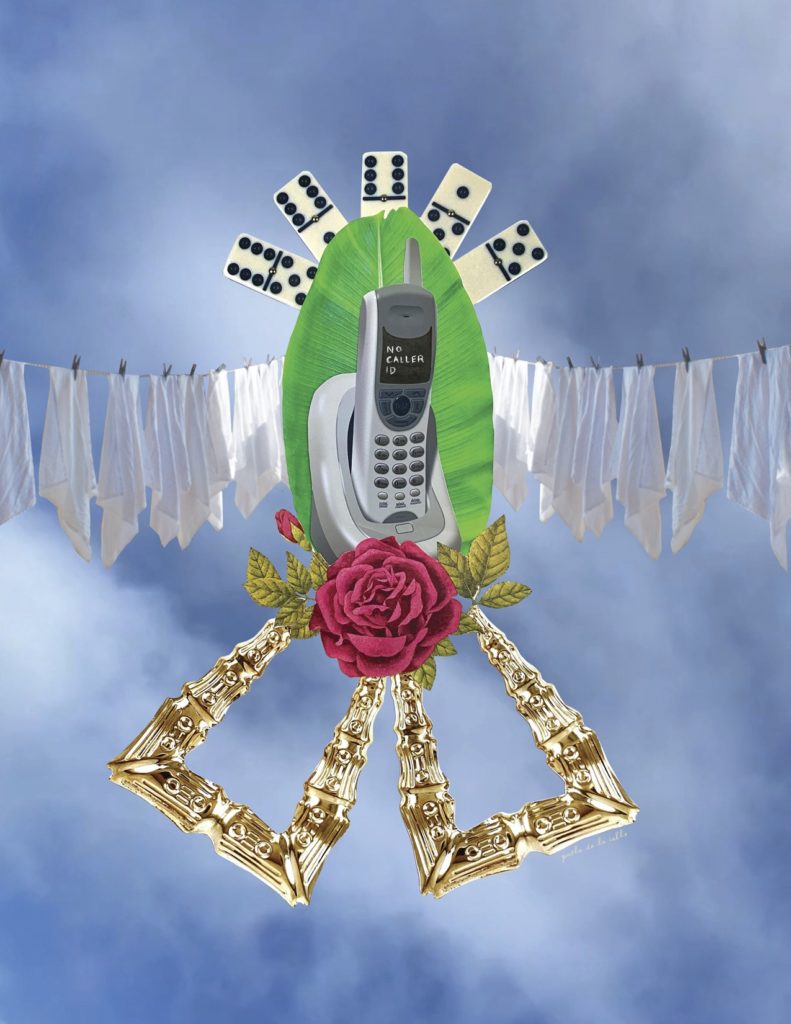

On January 26, 2026, I spoke with Paola de la Calle about her project titled Entre Azul y Azul (Between Blues). The work was installed at the windows of 596 Mass Ave in Cambridge, MA, back in 2020. Six prints displayed on the windows of a vacant storefront show a series of images: a phone with the message "No caller ID", mangoes next to a sign pointing to the cost of a phone call, clothes hanging from a laundry cord, and an ice freezer that says "Abolish ICE". Five years later, the artwork was removed. On October 7th, 2025, Entre Azul Y Azul was taken down.

Trump campaigned on mass deportations, and since assuming the presidency in 2025, ICE has been escalating its operations, setting arrest quotas and occupying sanctuary cities. Black and brown neighborhoods are being targeted by the Trump administration's immigration crackdown, in a show of racism and militarization.

"Since 6 January, roughly 2,000 ICE agents have been deployed to Minnesota under the pretext of responding to a fraud investigation. In practice, these largely untrained and undisciplined federal agents have been terrorizing Minneapolis residents through illegal and excessive uses of force – often against US citizens – prompting a federal judge to attempt to place limits on the agency’s actions." (Claire Finkelstein, The Guardian)

As of January 2026, in Minneapolis alone, three people have been shot by ICE agents. Renee Nicole Good was killed by an ICE agent on January 7th. Julio Cesar Sosa-Celis was struck in the leg a week later. Alex Pretti was shot and killed by ICE agents on January 24. (Emily Witt, The New Yorker)

"Entre Azul y Azul was created during Trump’s first term; it reflects that period, but it reflects the present as well. So while the artwork was taken down, the message still stands." (Paola de la Calle)

Romina: Could you tell us about Entre Azul y Azul? What is the inspiration behind the piece?

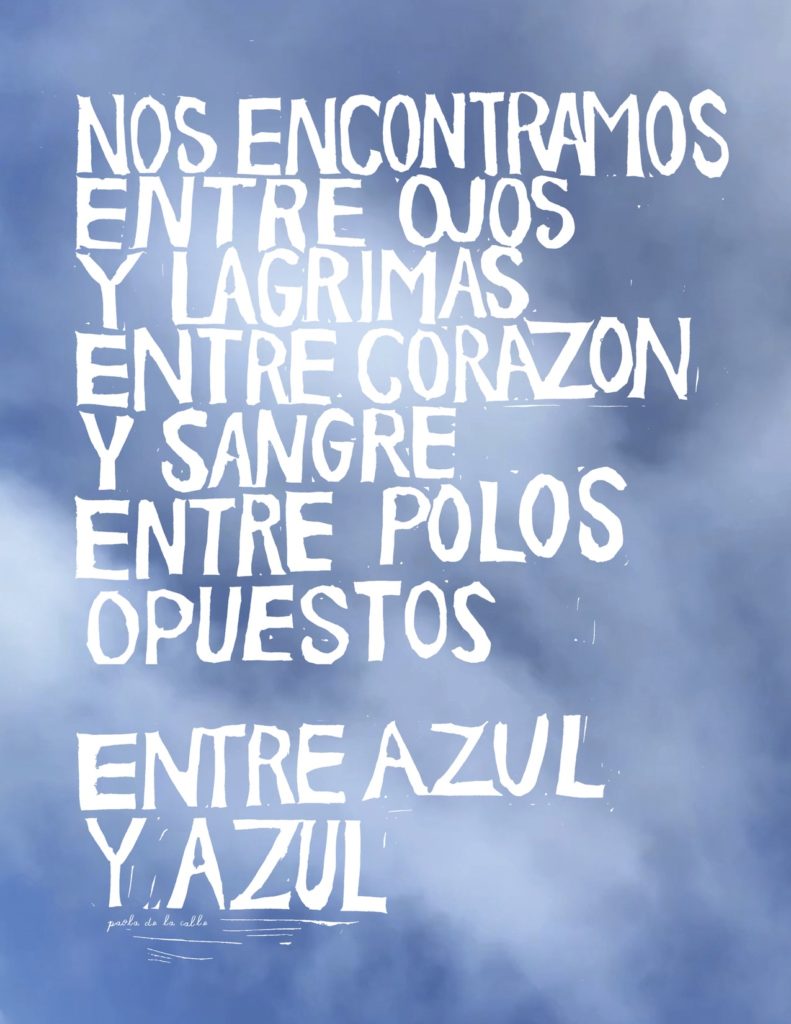

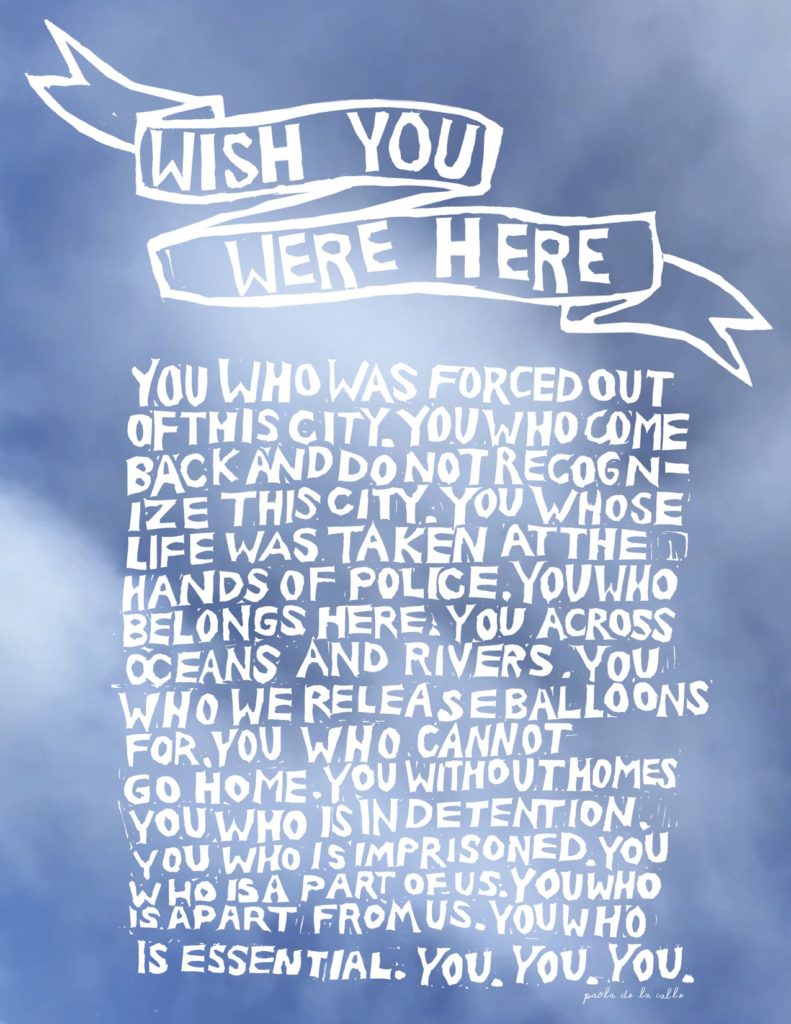

Paola: Entre Azul y Azul, or Between Blues, started as a poem. In my practice, I often write more than I sketch or draw in the initial stages–that's where the images start to develop. So Entre Azul y Azul started as just a poem.

It was 2020, so I was thinking a lot about distance and being away from people that you love. It was also a point where we were seeing a similar climate when it comes to immigration and state violence against people. So I was in a place where I was processing a lot and thinking about what it means to have these two blues, the sky and the ocean, be these two unifying forces. That's where the idea of Between Blues came from. When you're talking about being blue, it's about sadness, or sitting with the grief, which is a topic that I explore a lot in my practice.

It was during this time that I was invited to participate in the Central Square Business Improvement District's project to bring art to Central Square (in Cambridge, MA). This was a time when we were all inside, museums and galleries were closed, and people didn't really have access to art. So part of me really wanted to create a space where people could feel their grief was being acknowledged. It was not just art for art's sake, or making something beautiful just because, but making something that addressed the multiple layers of the moment in the city I grew up in, in a city that is heavily gentrified. So I started thinking about all the people I was missing, all the people who were pushed out, all the people who are no longer here, all of the lives that were lost to state violence. That’s where the poem I wish you were here came from.

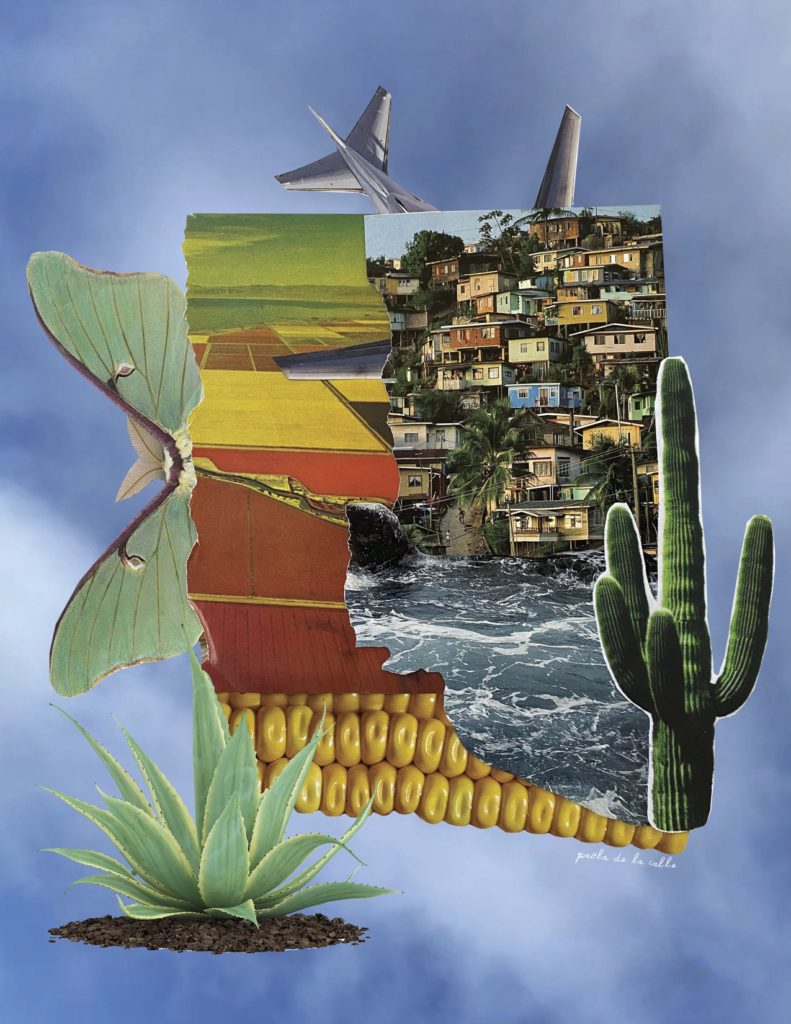

For me, the long process of carving blocks is meditative. It's a somatic experience that I'm moving through. It's very repetitive. Collage is really important in the artwork as well. It's this process of ripping things apart, about cutting and then reassembling. It’s reconstructing worlds or images of new possibilities. So collage becomes this technique that asks: how do we take things apart and build something new? And maybe some of the scraps can still come with us, right? Collage helps me think about how to rebuild and reimagine.

I tend to use a lot of images from National Geographic archives. I find it particularly interesting to use or pull from that archive, because old National Geographic magazines received a lot of criticism for their Western gaze, and you can see the extractive nature of their photography. I find that this idea of tearing, ripping, reimagining, reconstructing to be interesting to do with an archive that already exists, that within it perpetuates dominant narratives. A lot of the images that are on Entre Azul y Azul come from that.

There’s also my personal collection of film photos that either I've taken or found in my family archive, and a series of photos I've received from family via WhatsApp. I think that being able to work with an existing archive and using other people's contributions allows for there to be more than just one voice, which I think is really important, especially with public artworks. If they're going to be seen by many people, they should include multiple ways of seeing, multiple ways of understanding.

Romina: Thinking of the title, and it makes sense that the work started as a poem, there is this sentence about being in opposite poles, but between blue and blue. And I love the contradiction of it. Thinking blue and blue is the same color, so it should be equal, but you're speaking of different poles.

Paola: Yeah, even the line, “entre ojos y lagrimas” (“between eyes and tears”), those two things exist in the same place, so even if there's proximity, there can be a lot of space, and how do we exist in this space that's between us?

Romina: You’ve shared that you mix National Geographic images with your own archive, how do you go about selecting from it? When you think of your work, are the images something that appear similar in different pieces? Or do you have a specific selection for this particular one?

Paola: I've started to create a visual language, like a dictionary that I pull from.There are certain symbols or motifs that appear and reappear in my work. For example, in this work there's an image of a moth. And I've been working with the moth motif for a really long time. Maybe the first time it appeared in my work was in 2017, while I was more heavily printmaking. Then it reappeared in other forms, and now through collage. I really love the moth as this symbol for rebirth, or searching for light, or death. And not about death in the traditional sense, but about death as this process that we all sort of go through many times throughout our lives. I am thinking about a moth as a figure that represents a gaining of consciousness, or shedding ourselves, so that something else can be reborn.

When we're talking about migration, the symbol of the monarch butterfly comes up a lot because it is an insect that travels north. But we need to create new ways of engaging with the topic of migration. And I think it's the artist's role to start creating that new language and to figure out new ways to have that conversation. Because there needs to be multiple access points.

Romina: You mentioned grief when speaking about the work. I find it moving to know that there is a recognition of grief present, but you also mentioned belonging in one of the poems. How does belonging look like for you, and how does it appear in your work?

Paola: I think it's a constant question that I don't have an answer to. I can name what it feels like. The safety that comes with belonging or that there's an element of acceptance, of feeling seen, of love and relationships, closeness, and care. But I don't know if I can visually define it. This becomes an exploration of belonging. Because I also don't think that it looks one way for every single person. I think that belonging looks really different for all of us.

In my work, I try to approach quiet moments with a lot of care. Like, there's my grandfather's pajamas hanging on a clothes wire.

Romina: That's beautiful. I was wondering about what the laundry image was.

Paola: Yeah. That image was taken after his death. I had just arrived in Colombia and his pajamas were still hanging on the wire. So it's the remnants of this person, still there. And for me, it’s the quietness of a memory. I think memories help us belong, because then we can relate to a place or a person, or travel back to that moment in time. It is through those memories that we get relief. Like the feeling of nostalgia can also be this feeling of belonging. Especially because nostalgia has these rose colored glasses through which we look at things.

I think I'm searching for belonging within the works. And it feels like an exploration and a question.

Romina: Was Entre Azul y Azul your first public artwork?

Paola: I think so.

Romina: How did it feel seeing it in a public space?

Paola: I was in San Francisco at the time, when this was coming up, and I was watching the install happen through FaceTime, which is interesting because in 2020 we were doing that a lot. We were connecting through these digital spaces. But it's also a very common scenario when you have families across borders.

So, I was really proud to have this artwork up in a street that I grew up on. It’s a city where a lot of people that I love who grew up there can no longer afford to live there. There's an element of this that hopefully resonates, where people feel seen, that their existence matters.

There's a lot of responsibility, when your artwork is up in public. So I was really grateful to be trusted with the opportunity to have artwork out in the world and to see people interact with it.

I would always get videos or photos from friends when they were walking by. I had a friend tell me that when their friends come to Boston, they bring them to this mural. That was really special.

Romina: It's a way of long-distance communication, right? Sometimes I see people stopping by the window here at TAC and taking photos of your work. There is a connection being created between the studio, your work, and them, even when they are just passing by.

Paola: Yes. I think it's so important, especially since we live in a country where most of what you read while you're walking is an ad.

Public art is significant, you know? There's a lack of investment in it, and it's important to make sure that we create spaces for art to be displayed and to be free. The magic of public art is that it is for everyone.

Romina: And now, where would you like to see this? Or how would you like to see this work existing?

Paola: I'm really grateful that TAC decided that it was something that resonated with them, as an organization. Especially knowing that this artwork came down, because the owner of the building didn't want the work to be up anymore during this political climate, for whatever reason. I think it's important that we are vocal about where we stand because I don't think silence is going to protect us. It's important to be able to find spaces where people who want to abolish ICE feel comfortable stepping into. For me, it was less about my artwork getting taken down, but more about what it means in this moment to get artwork with this message removed. So I think my vision, or what I would hope, is that folks click the free link, download them, and put them on their windows.

You can download Entre Azul Y Azul HERE.

LET’S ABOLISH ICE.

Cover image credit: Knar Bedian.