AIR 17 Feature: Cici Osias

Nadege Pierre, Artist Programs intern at TAC, spent time with current AIR 17 resident Cici Osias:

NADEGE: Tell me about your artistic journey into textiles and photography.

CICI: I’ve always documented my life with photos. As a kid, I grabbed any device with a camera - whether it was my aunt’s old camera, my Nintendo DS, or an iPod touch. My love for archiving is where photography came into play. Growing up, photos had a strong presence around me. My family and I would constantly flip through family photo albums. In fact, my parents made a website just for my older sister’s baby pictures when she was born.

As for textiles, dressing myself has always been a preferred form of self-expression. In high school, I learned how to sew and made my first pair of pants. It was a pretty cool feeling to create my own garment, but I wanted the agency of creating the fabric itself. In college, I started researching Nigerian resist dyeing (adire), which was quite challenging to find information about. It's a technique passed down by oral tradition. I spent quite some time figuring out this process, watching travel vlogs and contacting people online about their methods. Gradually, I expanded to quilting, beadwork, and other traditional textile methods from my family’s lineage.

NADEGE: Speaking of photo archiving, you screen print remarkable portraits of you and your family on textiles. How do you select photos for storytelling? What's unique about this approach?

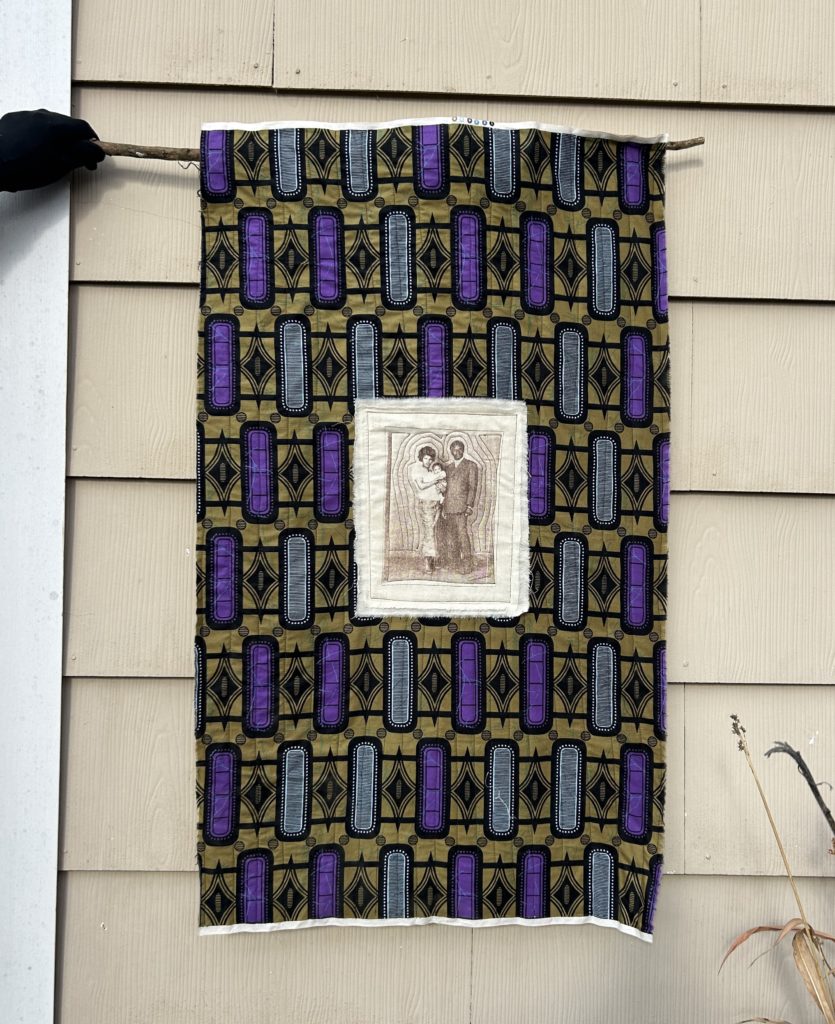

CICI: I recently explored screen printing for the first time, using fabric scraps from my collection and the TAC studio bin. It was a bit of trial and error, making test prints to see what worked and what didn’t. I screen printed my dad’s first portrait with my grandparents – taken in Kinshasa, Congo – on my textile called Portrait à Kin. This image reminded me of the Western African photography boom during the 1970s.

For Thanksgiving, while home in Baltimore, I immersed myself in old family photo albums. I found two baby photos of me sitting behind an iron railing, chewing on a Jenga block. The railing stood out to me because it resembled the Ghanaian Adinkra symbol of Sankofa, which means “go back and fetch it,” and represented learning from the past to build the future. The Sankofa motif is often depicted in my textiles. My brother also pointed out this symbol in the wrought iron gates throughout New York City. Its heart shape reminded him of the symbol that represents Erzulie Freda, the goddess of love and luxury in Haitian vodou.

I was able to put these symbol discoveries into context while reading Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad, a book about the codes concealed in African American quilt patterns. In West Africa, blacksmiths were often storytellers and knowledge keepers. They served a similar role in the US. Ornate ironwork was a symbol of wealth and status, so slaveholders commissioned blacksmiths to wrought large iron gates for their properties. Ironworkers could thus roam the land freely, familiarizing themselves with geography, and helped map out escape routes for other enslaved people. It was eye-opening to learn that American ironwork was infused with West African symbology, and notice the similarities between Ghanaian and Haitian motifs.

NADEGE: You recognize cloth as a vessel for storytelling. What techniques and materials do you use to narrate a story?

CICI: I mainly tell stories through the actual materials and use old, sentimental fabrics to create most of my work. My first ever appliquéd quilt, Et on danse, comme des garçons, was stitched with fabric from my first pair of pants I sewed back in high school and textiles gifted from family members. Another quilt, Erzulie and Her Offerings, was stitched with old bedsheets from my childhood home. My mom planned to donate those sheets, but I repurposed them to give them a new life.

Resist dyeing is another gateway into storytelling. Traditional Adire cloth is extremely motif based, using symbols to represent different animals or proverbs. With photography, I capture a moment rather than create it. Whether or not I took the photo, that moment would’ve happened. With quilting and dyeing, I get to create the moment or the memory.

NADEGE: Speaking of resist dyeing, what's significant about recurrent blue pigments, indigo and denim in your textiles?

CICI: It’s funny – blue is definitely not my favorite color, but used constantly in my work. My grandparents are from Congo, Nigeria, Haiti, and Black America, and my practice is a study of textiles and cultural traditions of these four places. I connect to my Yoruba lineage through Adire dyeing. Traditionally, made with indigo dye, Adire is a very rich shade of blue. I also think about the history of enslavement in the US, when enslaved people were forced to indigo dyeing. Those caught escaping from plantations were punished and placed in indigo plantations, where the life expectancy was merely five to seven years due to the harsh chemicals. I use the color blue in my work to pay homage to my ancestors.

NADEGE: There are three main tribes in Nigeria. Are there tribal fabric and dyeing techniques that you work with?

CICI: My family is from the Yoruba tribe. I tend to use the tribal technique Adire eleko, where a resist is painted onto fabric with melted wax or cassava paste. In Yoruba culture, textiles mark social status and community. Aso ebi, translated to family cloth, is a style of dress worn during celebrations where members of the same family or friend group wear outfits cut from the same cloth. I’m not too well versed in the traditions of other Nigerian tribes, but I imagine social status and religion also plays a big role in their textile cultures.

NADEGE: What are the most challenging methods and techniques you work with?

CICI: My work is fairly simple; however, obtaining knowledge has been a challenging process. All the techniques in my work were learned through research or passed down to me by my elders. Much of my practice I owe to collective wisdom. An artist named Dindga McCannon taught me appliqué quilting and shared many textile tips and tricks up her sleeves. With all of the textile knowledge I’ve amassed, I’m free to create what I want and share what I know.

NADEGE: I was intrigued by your astounding textile Toothpick Holder. Tell me about the concept of this unique piece. What inspired you to create this?

CICI: I had never made a self-portrait before, so last spring I decided to make one with my own smile. I wanted braces so badly when I was a kid; it felt like everyone around me was getting them. My dentist often recommended braces to close the gap between my front teeth, but my parents always refused. Eventually, my mom told the dentist that in Nigeria, where she’s from, tooth gaps are a sign of beauty. From that moment, I started to see myself in my mother’s smile, and the smiles of my family. While making this portrait I told myself, I can make my teeth sparkle all on my own.

NADEGE: As we start the new year with lectures on textile history and conservation, what other historical context impacts your artistry?

CICI: Research is a huge part of my creative process. My work is often foreshadowed by months of reading books on Black art, visiting museums, examining objects and other artists' work. I’m excited to learn in depth about West African textiles, and for Dr. Jonathan Square’s lecture “‘We Black Folks Had to Wear Lowells’: Negro Cloth, Enslaved People, and the Legacy of Lowell Manufacturing” in February. My journey as a textile artist started in 2021 with Adire research, while helping to design a class on the textiles of Atlantic slavery. I also researched Negro Cloth and West African textiles as a part of that process, and began to bridge the gap between textiles across the diaspora.

NADEGE: What are your favorite AIR classes? Any new techniques, materials you explored and incorporated into your work?

CICI: The screen printing class definitely wins. I walked in thinking the technique didn’t have much to offer me. But my perspective changed when I realized it could be used as a medium to recreate images that were personal to me. This class shifted my creative process and understanding of textiles as archives. Screen printing images feels natural to me, given that I was a photographer before becoming a textile artist. I also hope to incorporate a Congolese technique called barkcloth painting onto my work. These paintings were created by the nomadic Mbuti tribe of the Ituri forest, who pound the bark of the Ficus Natalensis tree and paint it with berries. I’m excited to figure out the role barkcloth will play in my future works.

As I mentioned before, clothing is my preferred medium for self-expression, but so is my hair. Within my work I’ve started to explore Black hair as a textile medium. Given the woolen quality and how Black hair lends itself to sculpture, I’m playing around with felting and weaving synthetic and real hair.

Another class I enjoyed is weaving. I’ve applied this technique to materials like raffia, inspired by the raffia weaving tradition of the Kuba Kingdom of Congo.

NADEGE: How has the residency contributed to your artistic development?

CICI: This is the first time I’ve had a proper, dedicated studio space. It's been transformative to have access to so many materials and spaces - especially the dye lab. I’m grateful and inspired to be surrounded by a community of people who are knowledgeable about textiles and consistently work on their crafts. Whether I need help burning a silkscreen or undressing a loom, people are always happy to lend a hand.

NADEGE: What do you hope to achieve after your residency?

CICI: I hope to have a firm understanding of my identity as a textile artist and the ability to tell my own story along with the stories of my people. I also hope to explore making textiles live outside; connecting with the land is a central part of my photography and textile practice. I want to create work outdoors and explore the world of public textile art.

Cici Osias (b. Baltimore, MD) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Her work draws influence from African American, Congolese, Haitian, and Nigerian motifs in order to make meaning of her identity and hold her people close. Within her textiles, Cici recognizes the role of cloth as a vessel for storytelling and traces the vestiges of shared origin and collective memory across the Black diaspora.

About the AIR program: TAC AIR combines studio access with a rigorous interdisciplinary curriculum, and regular critical dialogue, providing residents an opportunity to learn and explore the textile medium, and an alternative to traditional higher education programs. The residency culminates in a group exhibition produced and hosted by TAC. Since 2010, TAC AIR has graduated over 100 artists and designers whose work continues to further textile art within the fashion, fine arts, design and art education fields.

The Open Call for Textile Arts Center's Artist-in-Residence program is now live!

Deadline: March 06, 2026.