WIP Artist Highlight: 정다연 Dayeon Jeong

Nadege Pierre, Artist Programs intern at TAC, spent time with January WIP resident Dayeon Jeong.

NADEGE: What are you currently working on as a resident?

DAYEON: I'm revisiting my research project, in particular, a safflower dye sample from my thesis work in college. I was drawn back to this kind of pursuit because my thesis was naturally dyed. Throughout the process, I experimented across a range of colors, and safflower red gradually distinguished itself from logwood-iron black and others.

The physical process of dyeing with safflower and extracting the color, led me to research Korean and American archival material. I was drawn to wartime mapping and administrative documents, where red implicated how certain processes were documented, not symbolically, but as a bureaucratic marker.

In addition to dye, I began looking at other systems of notation. Diagrams recorded in the 악학궤범 ahak gwebom, a 15th century Korean musical treatise, visually informed me in how movement and hierarchy are transcribed. Dance and fabric operating as forms of architecture. The recorded logs were passed down and began to point back to mapping, cartography, and costumes in dance rituals. This residency is unfolding in a way I didn’t expect. I am finding myself returning to systems of recording, the ways materials, bodies and gestures are codified.

NADEGE: I am intrigued how you connect your materials with cartography. Is safflower dye (honghwa-yeomsaek 홍화염색 ) commonly used in Korean culture?

DAYEON: Safflower color has long functioned as an extreme marker of class. In Korea, people weren't allowed to access the dye, and its cultivation and use were highly state-controlled. There were specific departments in royal courts that managed it. Only artisans and master dyers knew how to grow and work with it. Safflower was preserved for royal ceremonial robes. So in this context, I was looking at royal drawings from the 의궤 Uigwe, the Royal Protocols, nearly 3,000 to almost 4,000 volumes of illustrated records. Royal court processions were notated in vermillion pigment, and books were bound in red silk or hemp cloth. With this project, I became interested in safflower red as an unstable, plural form that persists unevenly. For example, these scans on my desk, this Edo-period robe or this Joseon wrapping cloth, register such uneven conditions of the red.

NADEGE: You mentioned dance and fabric as forms of architecture. Do you position yourself in an architectural space when designing? Do you see yourself as a fashion or costume architect?

DAYEON: I really enjoy hearing the sound of that. I wouldn’t position myself within architecture in a formal sense, but I would like to see myself working through a kind of textile architecture. Plenty of architectural elements come into my work , especially when analyzing space and scale.

I examine how a costume with large sleeves can completely transform the space of a body. Looking at materials and comparing their use in different contexts feels architectural to me, in the sense of how our bodies relate to space and environment. When designing, I often think through materials such as rebar, with its associations of architectural armature and permanence, while working with fabric that responds to the body. I align myself with an engagement with architectural permanence, while using costumes or clothing as relational architecture for our bodies.

My design, Conical Interest, was informed by Gordon Matta-Clark’s ideas around architectural absence. He was an anararchitect who deconstructed existing spaces in New York, cutting completely through buildings slated for demolition. I was thinking about translating that logic to the body, designing with lantern sleeves, a 21-piece pant pattern mapping, and an metallic organza and taffeta ensemble that cuts and reorganizes space through movement.

NADEGE: How do you conceptualize your materials as a costume designer?

DAYEON: As a designer, I examine a lived bodily experience in movement and clothing. For a play called A Meal, I worked with an ensemble of actors with sizes scaling from 0 - 14, moving strenuously through a 3 hour performance.

I created aprons in 14 different ways for 14 different bodies. Even performers with similar choreographies wanted to move differently, so materials were developed relationally rather than uniformly. I used found materials and leftover fabrics scavenged throughout New York. There were vignettes performed across a multi-level theater, and the stage transformed between acts across the ensemble, I considered how the material, color and pattern could create a visual and relational hierarchy without fixing characters into rigid roles. White robes emerged for the initial scene where mystical creatures entered the space in a cleansing ritual gesture, first encountered by the audience.

In the final act, colorful and patterned textiles completely transformed the space alongside hundreds of ceramic artifacts.

NADEGE: Speaking of movement, I was intrigued by the fashion runway, When the Moon Waxes Red. Did you incorporate the same idea with the fabric and models?

DAYEON: Trịnh Thị Minh Hà is a postcolonial feminist scholar and filmmaker, and When the Moon Waxes Red referenced the title of her work, where the representation of minoritarian subjects is described with tinging red, moonlight, and reflection. It felt poetic, but also marked by convergence and collision, something luminous yet foreboding. The movement of fabrics became the vocabulary; I referenced Korean shipmaking and warships, billowing masts. I thought about the tension of limbs yielding and straining. There was a movement of resisting, embracing, letting go; a constant tension and fluctuation.

NADEGE: Natural objects, like beetles and other insects inspired your work. What was your design concept for Travel Story, Minor Rage, and On Shattering Vessels?

DAYEON: I collaborated with a dear friend around the idea of a travel story. The play followed a bug moving through a forest on a journey of transformation. We discussed transitions of gender or identity through design that mimics shedding and continual reformation. Insects mayflies came to mind; they shed up to 50 times in their lifetime. Patterned, pinstriped, checkered wool was used to register metamorphosis and shifting allegories of the characters.

The Minor Rage was a deconstruction of an foundred bridesmaids dress, mapped with aerial bauxite extraction pool grids. I was looking at the work of Luzene Hill, who used knotted Inca quipu cords and cochineal beetles in her practice. Her engagement with rage and sexual trauma resonated with me. I researched the unequal gendered impact of colonial bauxite extraction, using female beetles to traced the glimpses, rages of women globally.

On Shattering Vessels was another term project developed through museum-based research. We looked closely at the work of the Korean-Canadian artist Zadie Xa. Her work references shamanistic rituals through large-scale costumes and hanok structures. My classmates and I interpreted those ideas through chrysalis structures that suggest emergence.

NADEGE: Scrolls are cultural artifacts that record life events. What was significant about Ch’onhado (All Under Heaven) 23-foot scroll?

DAYEON: One panel of the scroll draws from a Ch’onhado map, which articulates a quasi cosmological worldview where China is positioned at the center. The rest of the world appears peripheral. I was interested in bringing together multiple mapping systems rather than treating Ch’onhado as a singular framework I began thinking about the scroll as a long strip of film with arbitrary cuts rather than a seamless continuity of history. The installation was positioned at my eye level, then lifted to 12 feet. Viewers could encounter the work at different heights and in fragments. Twenty five panels were printed on kozo paper and silk georgette, forming a single extended surface rather than discrete panels.

NADEGE: Your design, Patternbook Jido 지도, was quite different from other projects. How did you pattern Korean history around a skirt?

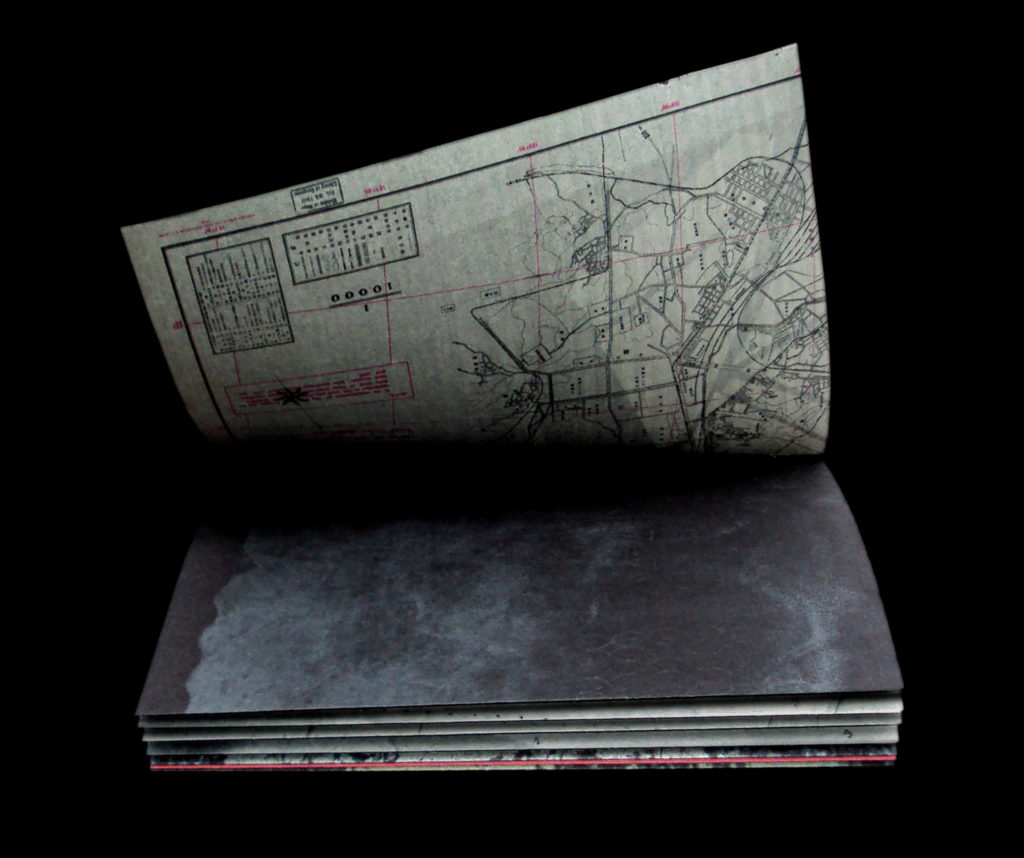

DAYEON: Jido means map in Korean. I made a large scale poster, overlaying many different types of maps. The first layer of the map that was most apparent was an abstract-like skirt pattern made for my thesis. This personal skirt was made with lines and seams drawn from diagram-like kites. I was looking at how organic, but arbitrary signs, lines and borders were. Then, I encountered this military map during World War II US military’s occupation in Korea. How arbitrary those kinds of the same lines and borders in that case were. I was kind of imposing all those images. There’s a very faint layer of this naval strategy diagram that was showing how to maneuver in the naval waters. In broad strokes, I’m thinking about colonialism, ecology, and curious about mapping, notation of knowledge and the recording of it. I bring my design concept from translational to more personal and intimate. This kind of scaling is interesting to me. My research for the skirt became lines that intersected at a point on a map, which continued in their own directions.

For the remainder of the Patternbook series, I used materials that were available to me, such as silk chiffon and Georgette fabrics. The maps were digitally printed on Kozo paper, similar to rice and mulberry paper for the newsprints. A mystical, historical map was used on the third or fourth panel. It pointed to all these alternate world views and mapped from cartography. I used a map from my childhood home that has been there constantly throughout my whole life. Precisely, I did not even know what the map was. The map traveled with our family when we moved to different homes. It’s been somewhat peripheral.

NADEGE: What fashion or costume maps would you leave for us as lasting legacy to navigate or unravel?

DAYEON: I don’t want to presume that I have something to teach people. I feel like through excavating this history for me personally, I can see many ways of documenting, recording, and transmitting knowledge, Whether it's music, fabric, costume, royal rituals and processions, there's always this kind of implication within, in relation to all these other current systems. So I feel it's not so much that I'm going to read more about Korean history, but more about local or collective history.

NADEGE: We are looking forward to your textile dyeing workshop: Resurgent Rhizomes: Knotweed & Dyeing Invasive Histories on January 31st. What's unique about Japanese knotweed?

DAYEON: Knotweed weed is similar to safflower, where natural dyes are reactive and shift tones. It resembles iron and pH scales changes at a time. It’s unstable and local in Gowanus. Along the Gowanus Canal, there are reed beds forming and easy to spread. It’s an invasive species in New York that piques my interest. I see them throughout my neighborhood.

정다연 Dayeon Jeong (b. Los Angeles, CA) is a New York-based conceptual artist working across textiles, printed matter, installation and experimental costume design.

Her ongoing research and material practice engages patternmaking and safflower dyeing to explore Korean historiography, colonial cartography and textile tradition. She is interested in how bodies and sites are mapped and remembered across personal and imperial scales.

Dayeon earned her BFA in Fashion Design from Pratt Institute in 2024, where she was a Geraldine Stutz Scholar. Her thesis collection, When the Moon Waxes Red, was showcased at Powerhouse Arts and featured in publications including Hypebeast, Vogue Runway and Fashionista. Her performance and theater costumes have been staged in productions at HERE Arts Center and The Tank. Most recently, she received the Windgate Fellowship as a 2025 Visual Arts Fellow at the Vermont Studio Center.